Some artists find representation without having searched for it: a gallery approaches them on their own. Maybe they saw someone’s work at the art school’s open days, or a professor or mutual acquaintance mentioned the work. Either way: this is rare. If you haven’t been approached by a gallery, but want to establish contact, you need to work on expanding your network. This will help you to create organic engagement opportunities.

Consider the following strategies:

- Understand the gallery’s network, and embed yourself within it: Understand which artists and gatekeepers the gallery is surrounded by, and see whether you can gradually increase contact with them. This is easiest done at gallery events (openings, artist talks, curated tours, art fairs, etc), where you can listen in, observe and judge. Attending these public events creates the chance to get invited to the more private circles that often happen alongside: an opening dinner, or drinks in the gallery’s back room. These occasions are not meant for you to push your work; rather, they should serve as a platform to understand the gallery’s environment, and to organically establish connections. The more intimate the setting you get into, the less the situation will be about you. Understand that everyone usually has an agenda to push: the gallerist might want to generate sales or network with guests; the staff might be busy attending to collectors; fellow artists might see a curator they’d want to talk to. That’s why you want to be both natural and sensitive whenever you get invited to an “inner circle” event: you don’t want to come across as pushy or needy.

- Understand your supporters and their potential to gain gallery awareness: We all know people with connections; your existing network might include artists, collectors, professors and assistants, family and friends, etc. If you’re lucky, one of these has a direct connection to the gallery you’re interested in (or to a gallery you don’t yet know of). Maybe one of them is interested in highlighting your work? While directly asking someone for such a favor puts them on the spot, sometimes supporters think of this on their own. This drastically changes the dynamic to your potential advantage: it’s nearly impossible for an artist to approach a gallery, yet a third party can often manage this without resulting in weirdness. Understand that while some supporters won’t be interested in helping you, others might do it in pushy, detrimental ways. Ideally, the third party checks back with you, to understand how to adequately highlight your work to a gallery – which henceforth knows about you. This doesn’t guarantee their professional interest, but helps to connect a step further: you’d now be more visible than before. This is true even if they forget about you, since the next time someone drops your name, they are more likely to remember it.

- Connect to the gallery’s represented artists: While anyone in your network can be helpful in generating gallery awareness, a gallery’s represented artists can often be a natural point of contact (this can be especially true if your network doesn’t feature anyone else who might be able to help you). Can you connect to some of them? If you don’t know any of a gallery’s represented artist yet, consider visiting the gallery’s public events to gradually try to change that.

Once you naturally jell with someone, the mutual interest for each other might result in worthwhile discussions about each other’s work, the state of the art world, etc. Drinks might follow. Studio visits. These kinds of first steps could lead to mutual support (when installing shows, moving studios, needing advice, etc) or even friendship; they could lead to collaborations on specific works or exhibitions, which sometimes can generate the galleries’ awareness of you. Understand that your efforts will usually only be as efficient as they are authentic: faking interest in artists (to get their galleries’ attention) will rarely work out, and has the real risk of you coming across as egoistic and unlikable. As with all networking efforts, it’s best to do them in a way that inherently feels good to everyone who’s involved; this way, the process rewards itself.

Don’t ask represented artists to highlight your work to their gallery. They might feel their trust betrayed, might see you as competition, or might simply not feel comfortable proposing a business deal to their gallery (read the comments at the end of this chapter for details). - Expand your general network: Instead of directly aiming for a gallery’s attention, expand your general network to include various layers of gatekeepers: local artists, curators, art writers, non-profit venues, etc. This long-term strategy strengthens your position in the local art scene, and makes it more likely for you to get to know someone of the gallery in question. The art world is fluid: people leave their jobs to work at other places (institutions, other galleries, non-profits, etc), and in other functions: an assistant from three years ago could be tomorrow’s gallery director or head curator of an institution you’d like to collaborate.

- Consider non-local galleries and networks: Instead of looking for local galleries only, consider which non-local artists you know. Are they connected to galleries, non-profit art spaces, or do they curate on their own? Visiting them might expand your network in entirely unexpected ways, with the additional benefit of you getting to know another art scene. Maybe your contact can tell you about galleries that might be of interest to you? Find out about efficient scheduling: a week with many openings or an art fair can lead to dozens of organic networking opportunities.

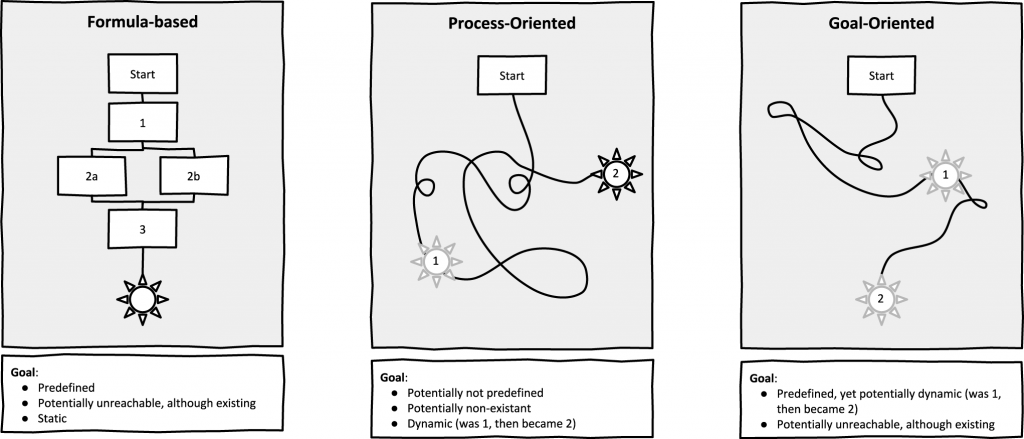

Instead of connecting to non-local artists in your network, you can also research the represented artists of specific non-local galleries. Consider reaching out to them: maybe there’s time for a meeting or studio visit to discuss their work? In case of actual curiosity on your behalf, this can be a potent way to expand your network, and potentially, over the years, even get the gallery’s attention. While finding a gallery might be your driving force, refrain from solely judging your efforts by the outcome (to have found a gallery representation); instead, focus on the process: to have gotten in touch with fellow artists and their work. You can never know what this will bring to you in the upcoming years. - Spot disinterest: Understand that you can’t force interest in you or your work. While in your mind your work might be a perfect fit, this doesn’t say anything about the realities and interests of the gallery in question. As with dating, it takes two to tango. When you notice conversations or situations to be imbalanced (gallery staff interrupting you, not listening or being attentive, etc.), then accept this disinterest. You can try to see whether over the months, someone else in the gallery shows more curiosity, or whether a specific person simply was in a bad mood; but understand that mutual likeability is random, and often can’t be influenced. Don’t let this frustrate you, but accept such implicit rejections, and continue your search elsewhere.

Refrain from asking others to highlight your work to galleries. Even though you might envision this to be easy for them, you simply cannot know, which usually makes it inappropriate: It puts the burden on someone else, and asks for quite a commitment to your work: even if the person you ask truly likes your work, they might not feel comfortable highlighting it to others – especially to potential business collaborators. Asking others to push your work is usually not organic, but forceful: a demand that puts someone on the spot, requiring them to either comply or shy away – both resulting in a weird power imbalance. Trying to be your own brand ambassador is more respectful and sensitive, and has the advantage of personal growth and control about how external parties are approached. Instead of asking someone to highlight your work, wait and see whether they might offer this on their own. Don’t expect it though: it’s unlikely to happen.