„Es ist kein Film, es gibt kein Drehbuch, keinen Konflikt und keine Auflösung.“

Tim Eitel [1]

I.

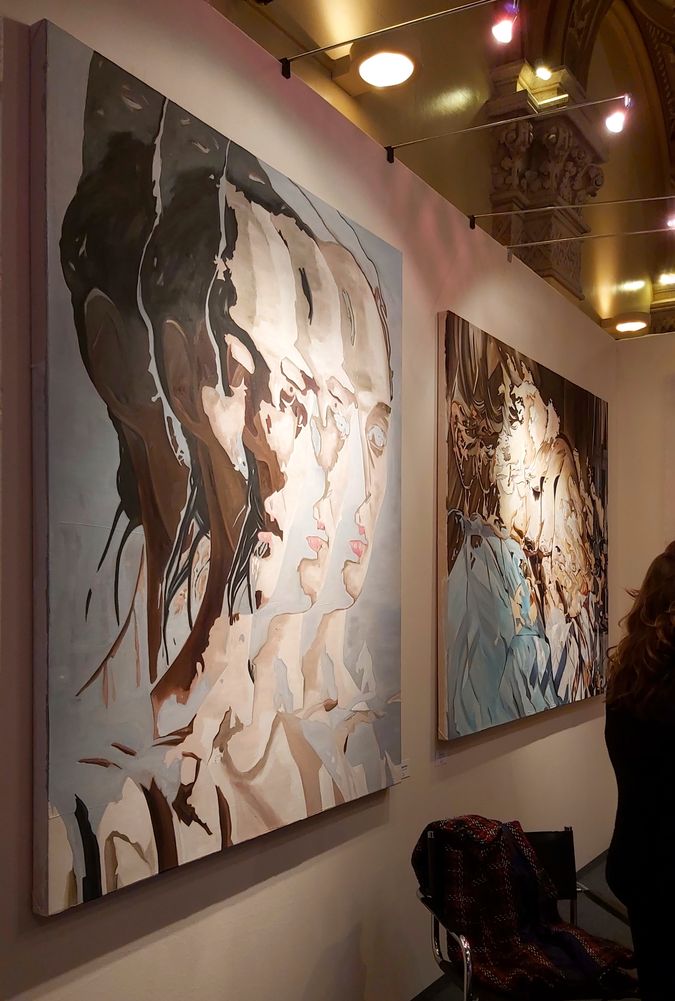

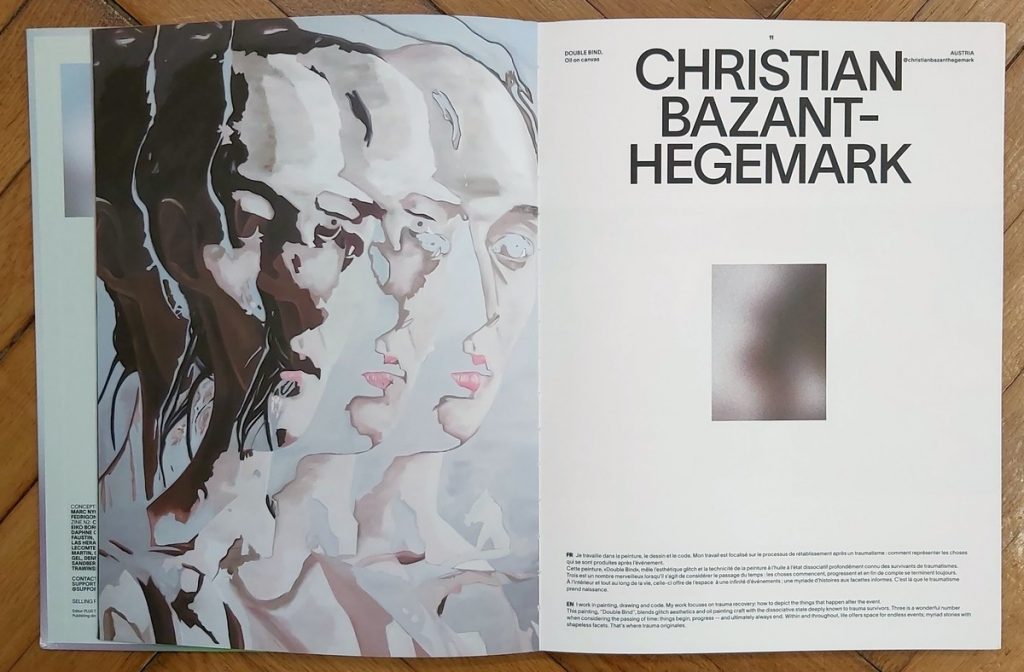

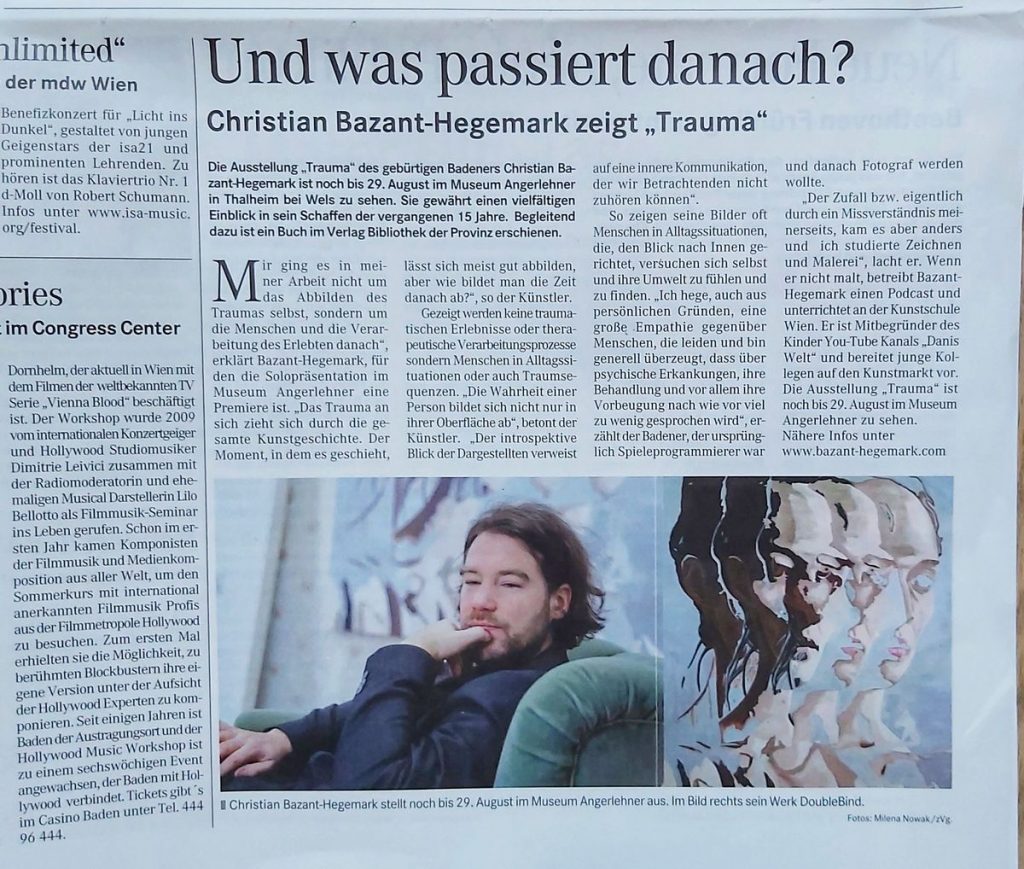

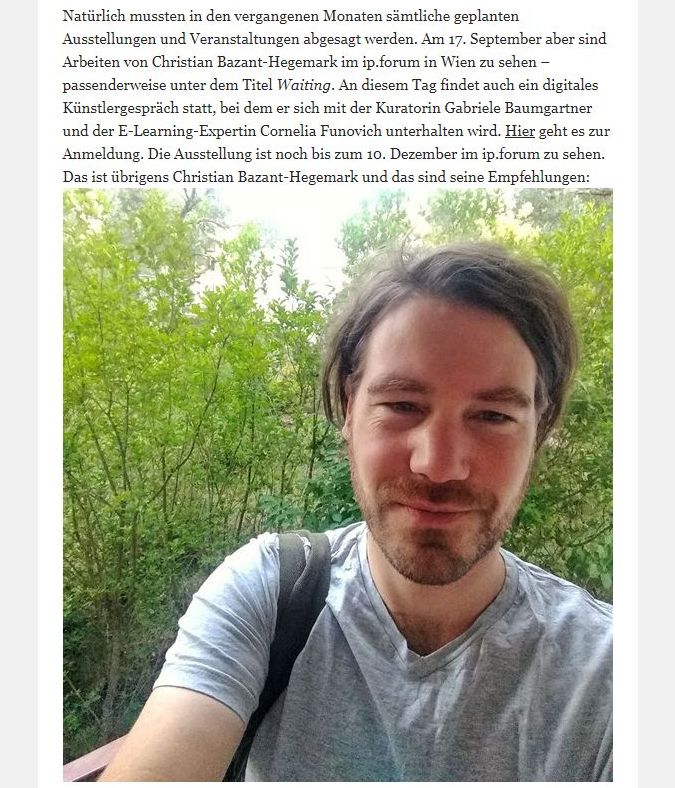

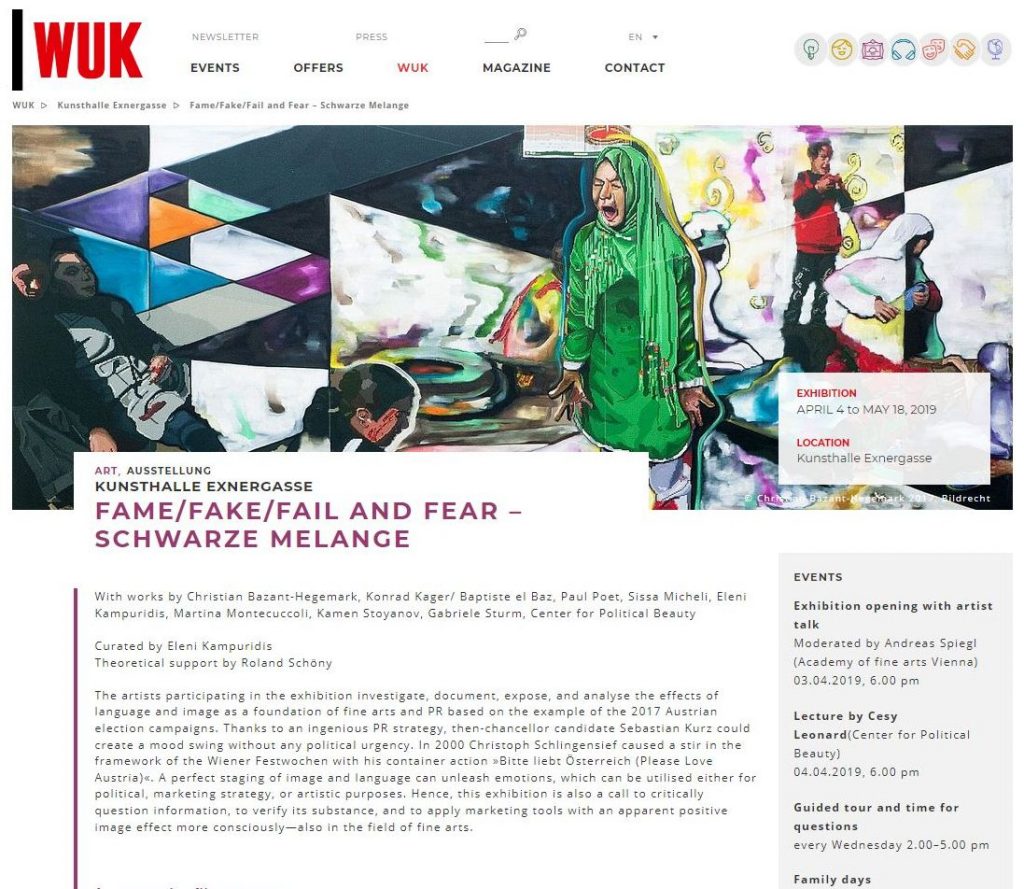

Wie positioniert sich die Malerei in einer Welt, in der sich die Rolle des Bildes grundlegend gewandelt hat? Lange Zeit hatte die Malerei das Monopol auf das große, farbige und wirkungsmächtige Bild. Dann wurde sie von der Fotografie als neuem Leitmedium des Bildes abgelöst. Dennoch blieb die Malerei bis weit in das 20. Jahrhundert das unumstrittene Hauptmedium der Kunst. In den letzten Jahrzehnten hat sich das aber nachhaltig verändert. Die Wahrnehmung der Welt ist multimedial geworden. Auch in der Kunst. Ist die Malerei oder auch die Zeichnung in unserer heutigen multimedialen Gegenwart noch zeitgemäß? Als Betrachter der Arbeiten von Christian Bazant-Hegemark habe ich zwar den Eindruck, dass diese gern gestellte Frage in seinen künstlerischen Bildwelten mitschwingt, ihr letztendlich aber keine allzu große Bedeutung zukommt. Der Künstler will sich nicht für sein an sich traditionelles Medium rechtfertigen, das gemalte Bild muss nicht beweisen, dass es noch mithalten kann mit den Bedürfnissen und Anforderungen unserer Zeit. Seine Kunst hat etwas Selbstverständliches und Ungezwungenes, will nicht gefallen oder vordergründig Bedeutung oder Aktualität suggerieren. Die Malereien und Zeichnungen sind einfach da und biedern sich nicht an, möchten nicht einem bestimmten Zeitgeist oder Trend Folge leisten. Und doch sind sie in ihrer inhaltlichen wie formalen Ausrichtung nur heute, in diesem Hier und Jetzt, so möglich.

Nach Robert Fleck leben wir in einer Epoche tiefen Umbruchs in der bildenden Kunst, in der die Vorschreibungen, die in den Köpfen verankerten Regeln und die Formensprache der klassischen Moderne des 20. Jahrhunderts und ihrer Nachfolgebewegungen nach Jahrzehnten ihrer Abarbeitung zum ersten Mal kein Problem mehr darstellen. Gleichzeitig würden, so Fleck weiter, gerade in der Malerei der letzten Zeit derart viele neue Dinge versucht, erprobt, sukzessive in Stellung gebracht und auch durchgesetzt, dass man heute von einem neuen Bildraum und den Umrissen eines neuen Paradigmas in der Malerei sprechen könne. Dies zeige sich insbesondere in einem Zwiegespräch zwischen der zweiten und dritten Dimension, einhergehend mit der Auflösung der zweidimensionalen Bildstruktur und einem Atmen und Pulsieren, oder – wie Fleck es nennt – einem „Floaten“ des Bildraums. Ob er hier auch Werke wie jene von Bazant-Hegemerk im Sinn hatte?[2]

II.

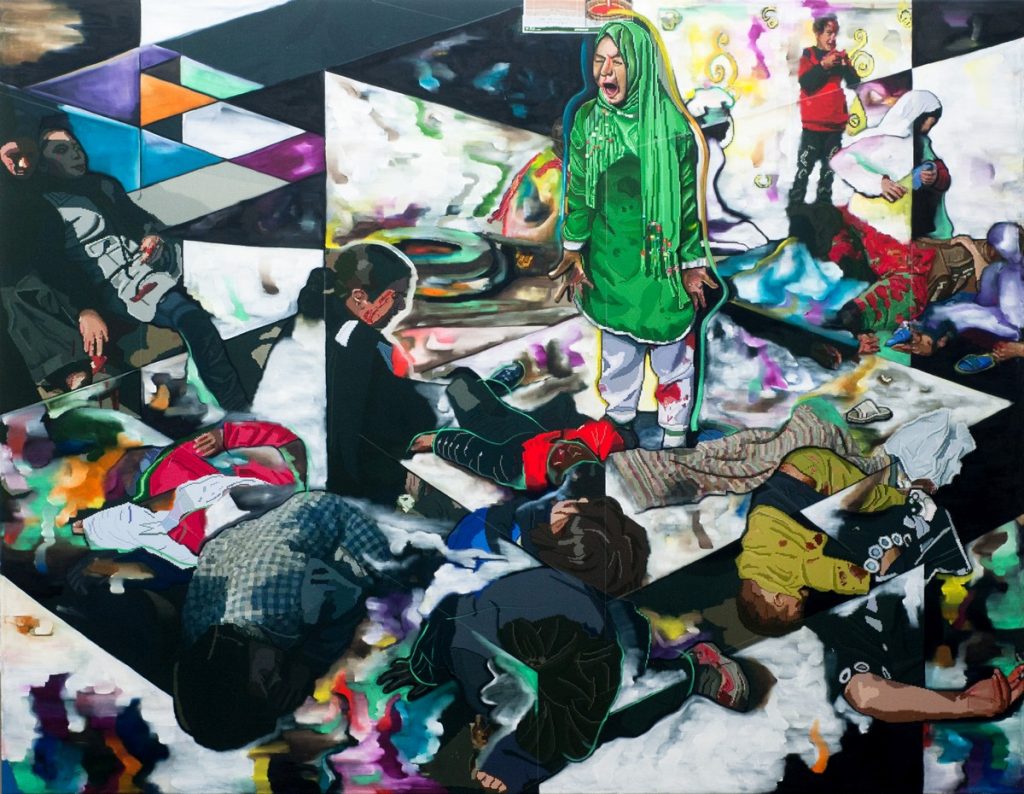

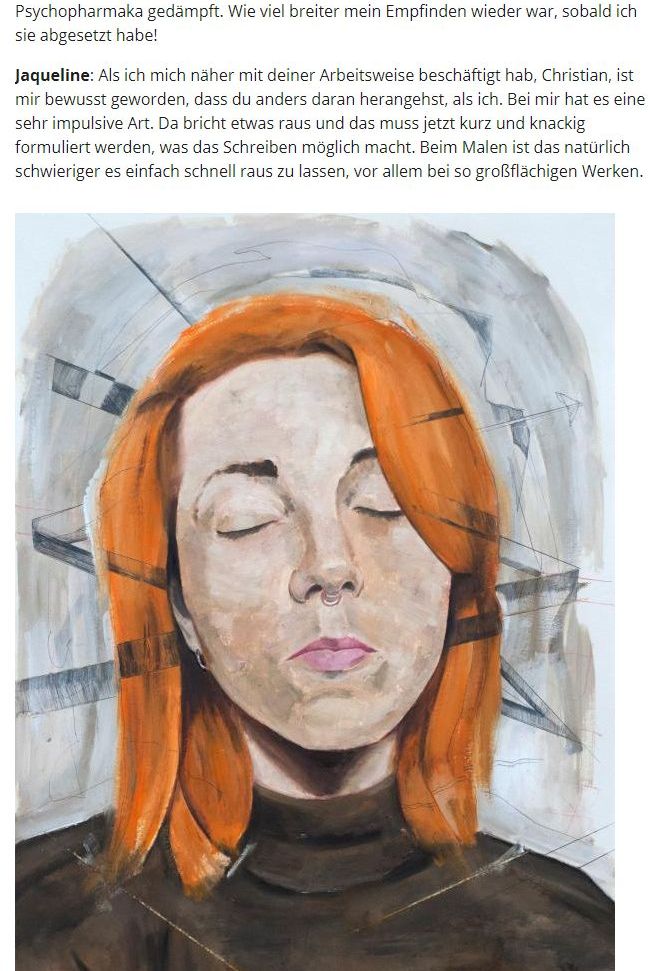

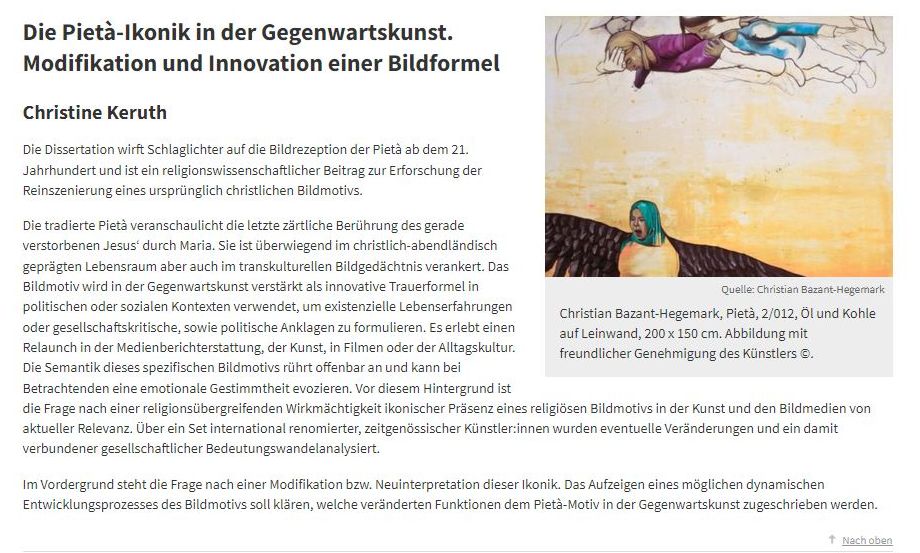

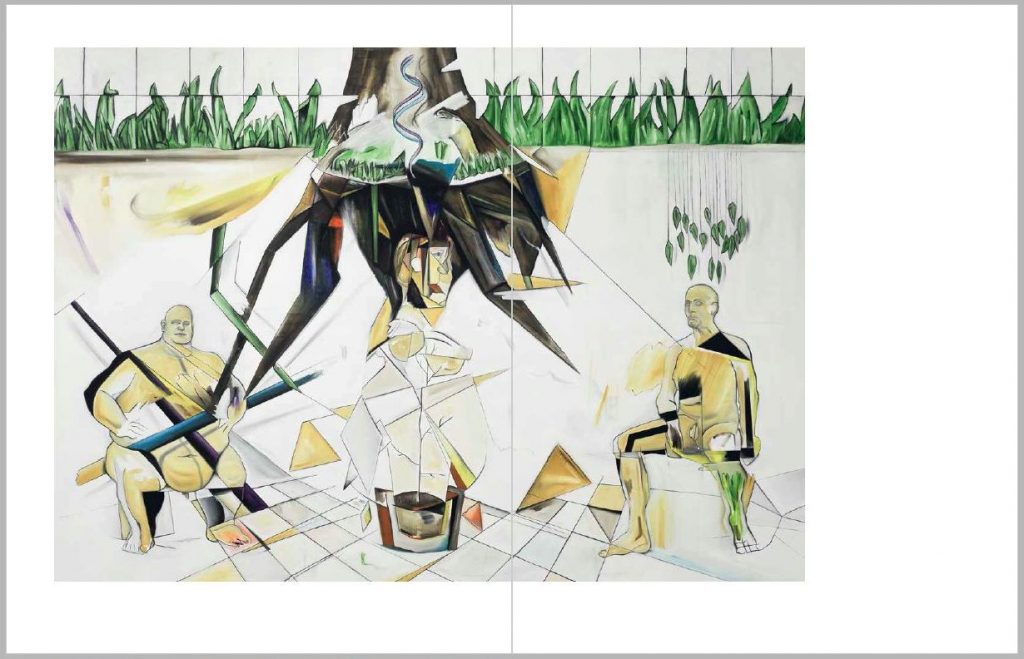

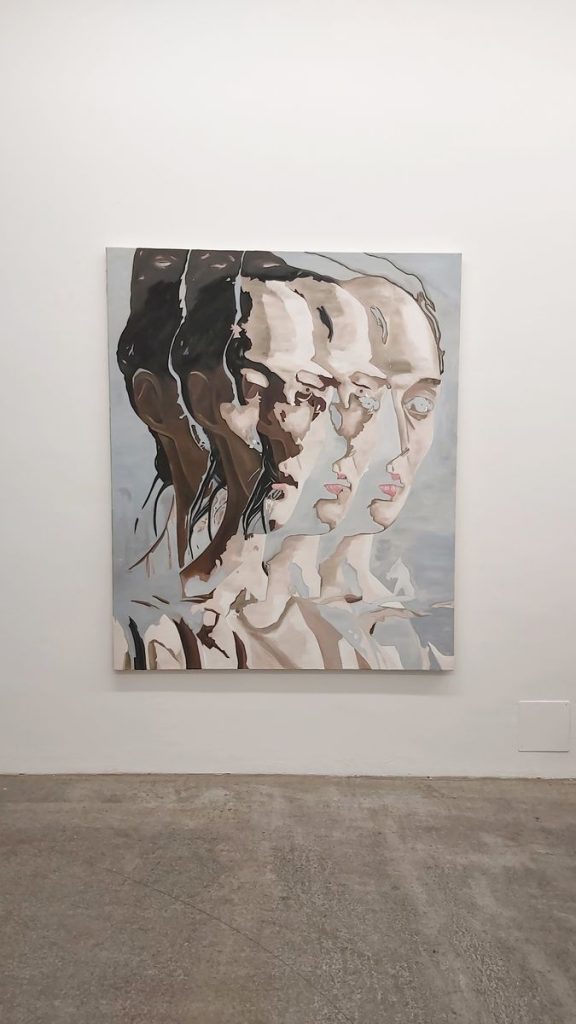

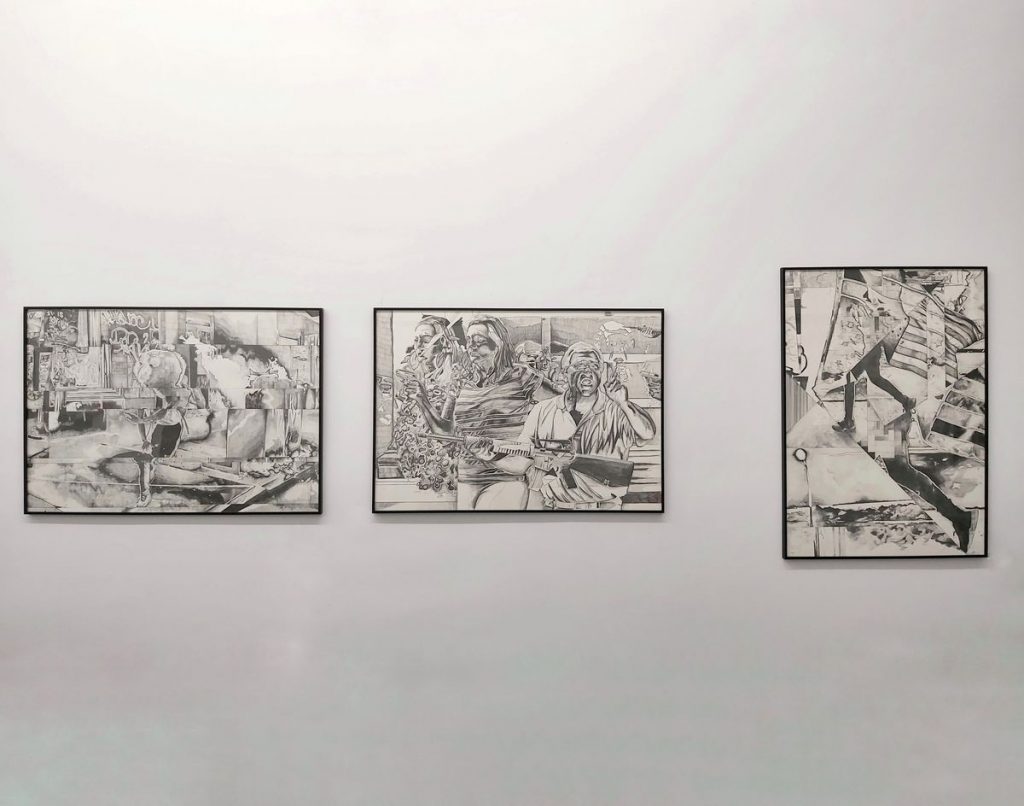

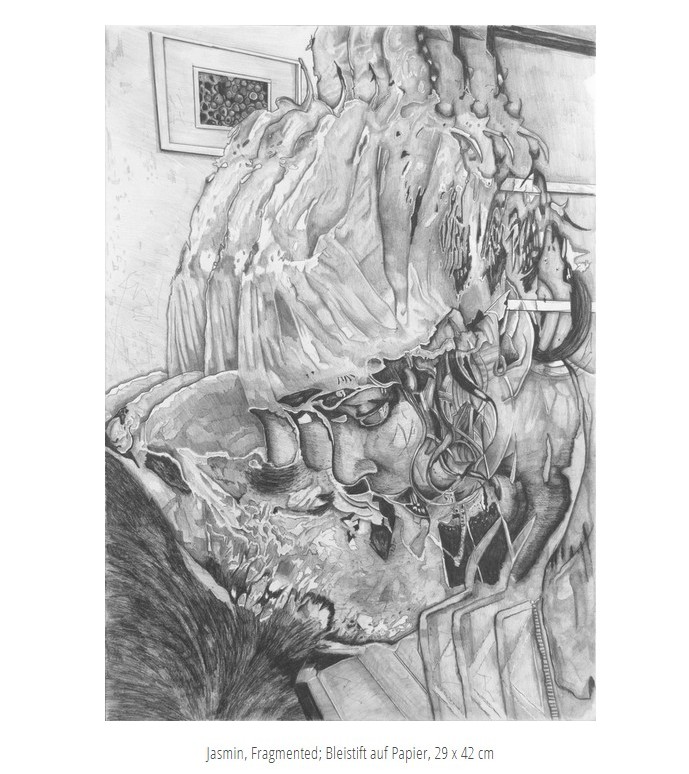

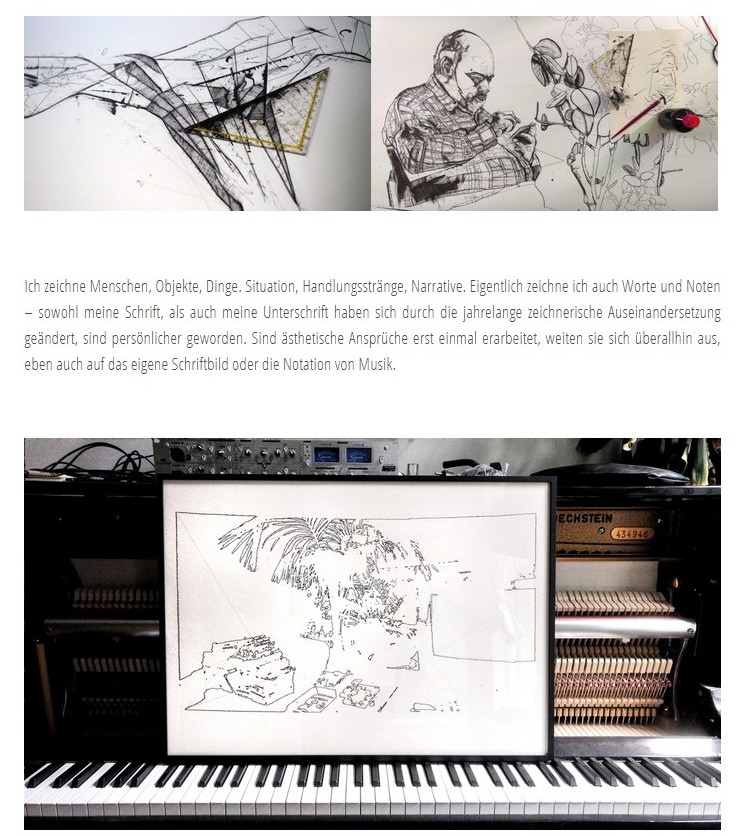

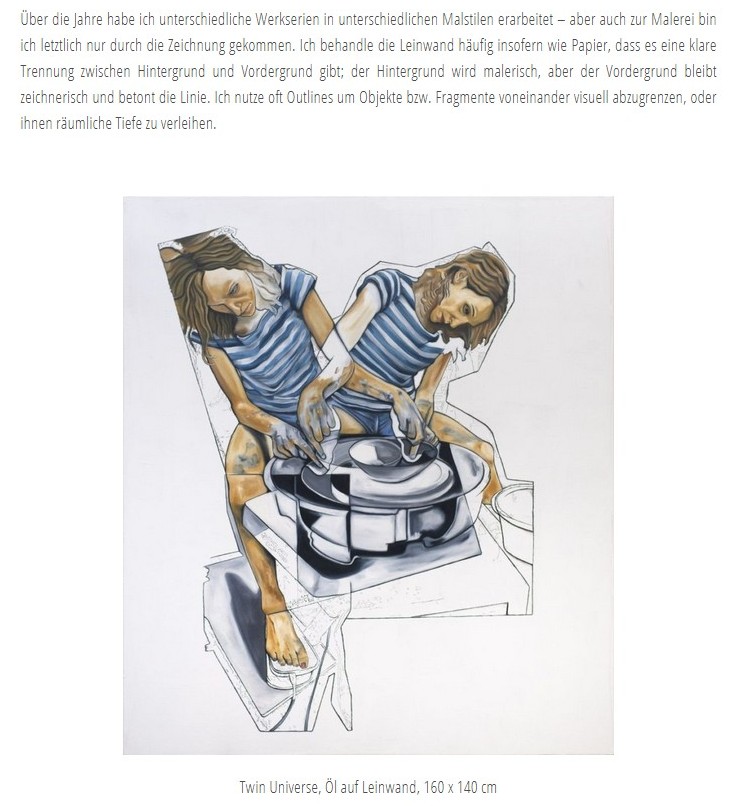

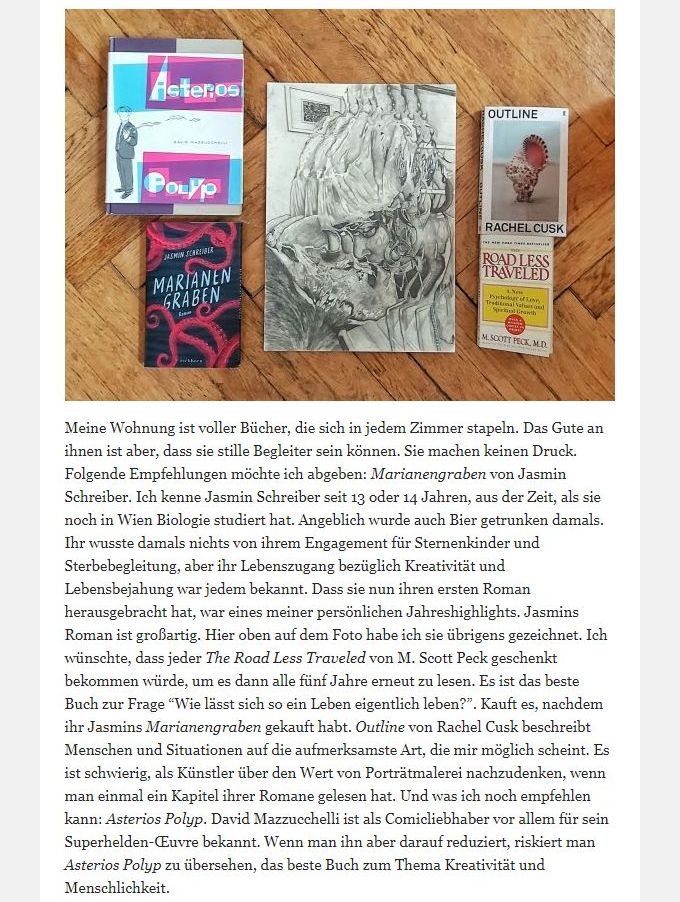

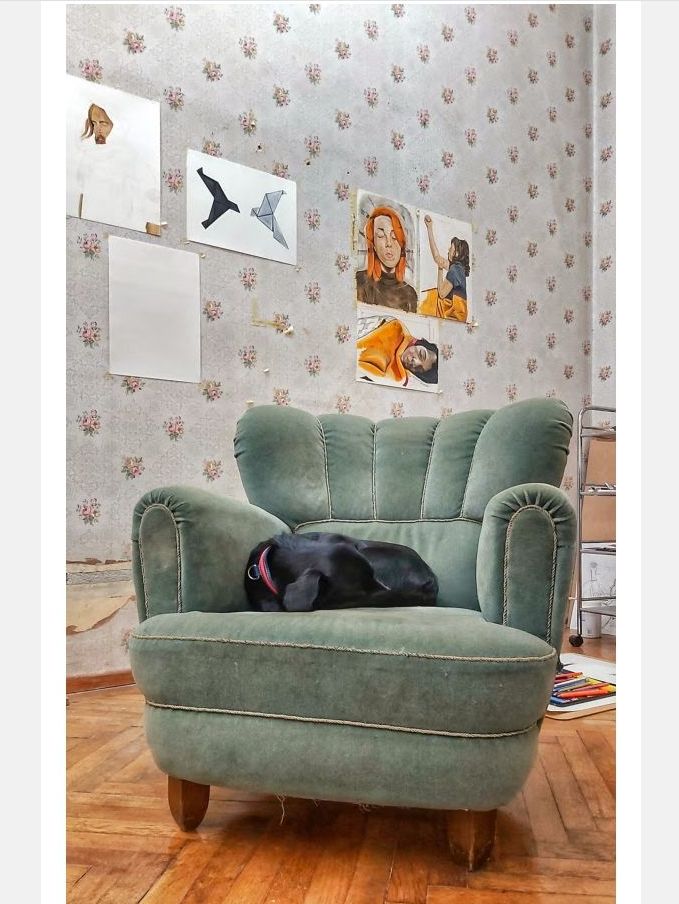

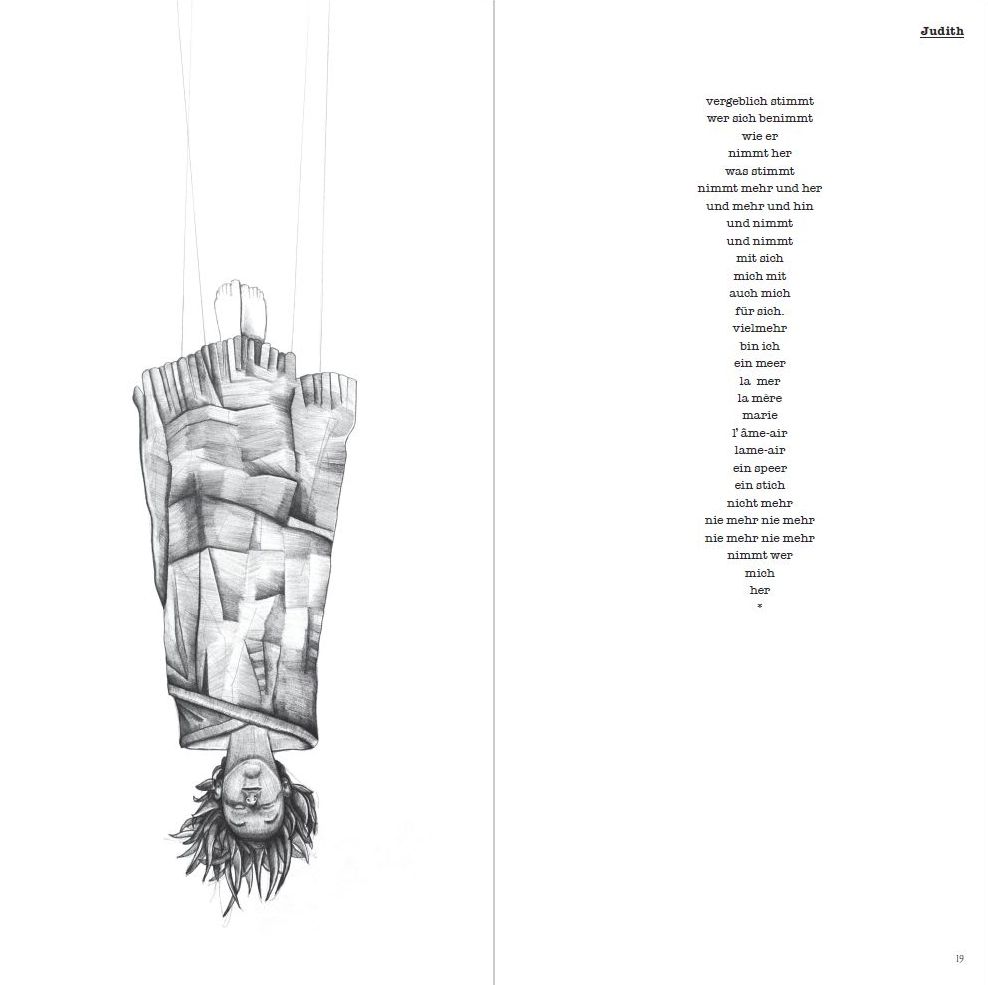

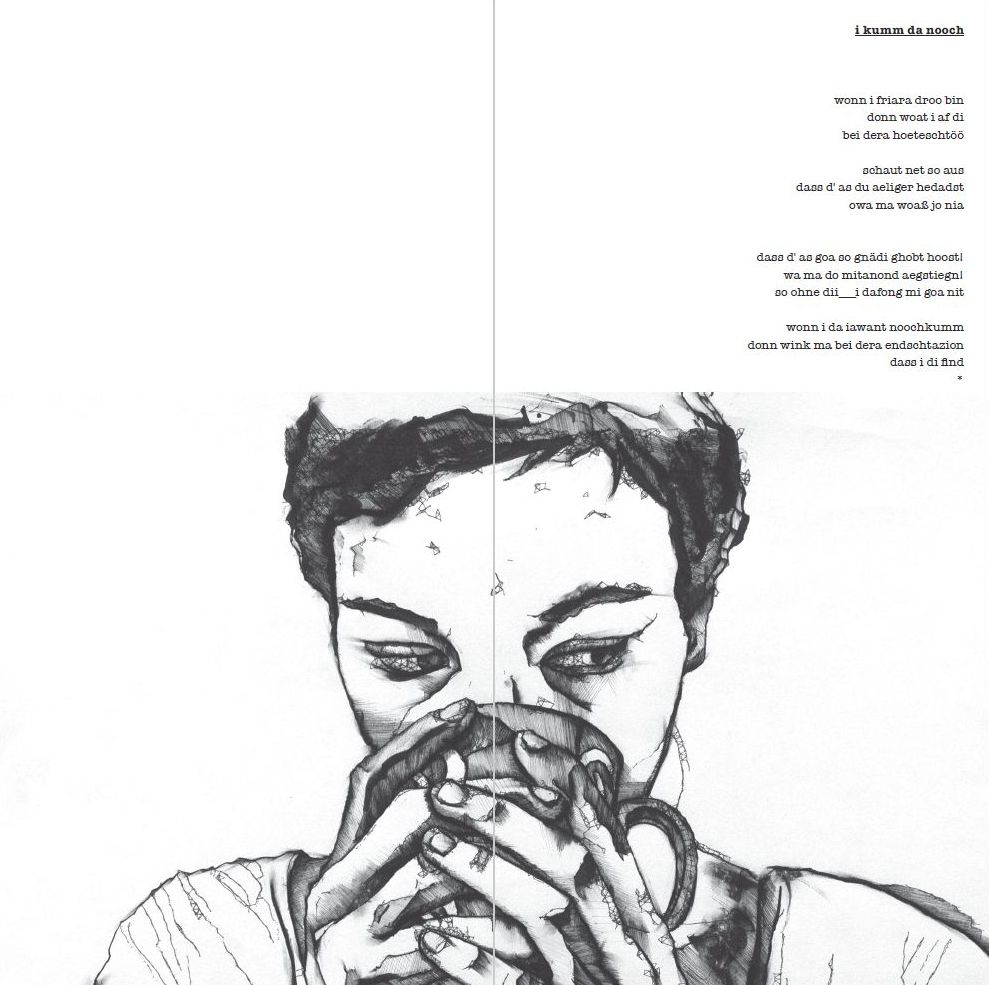

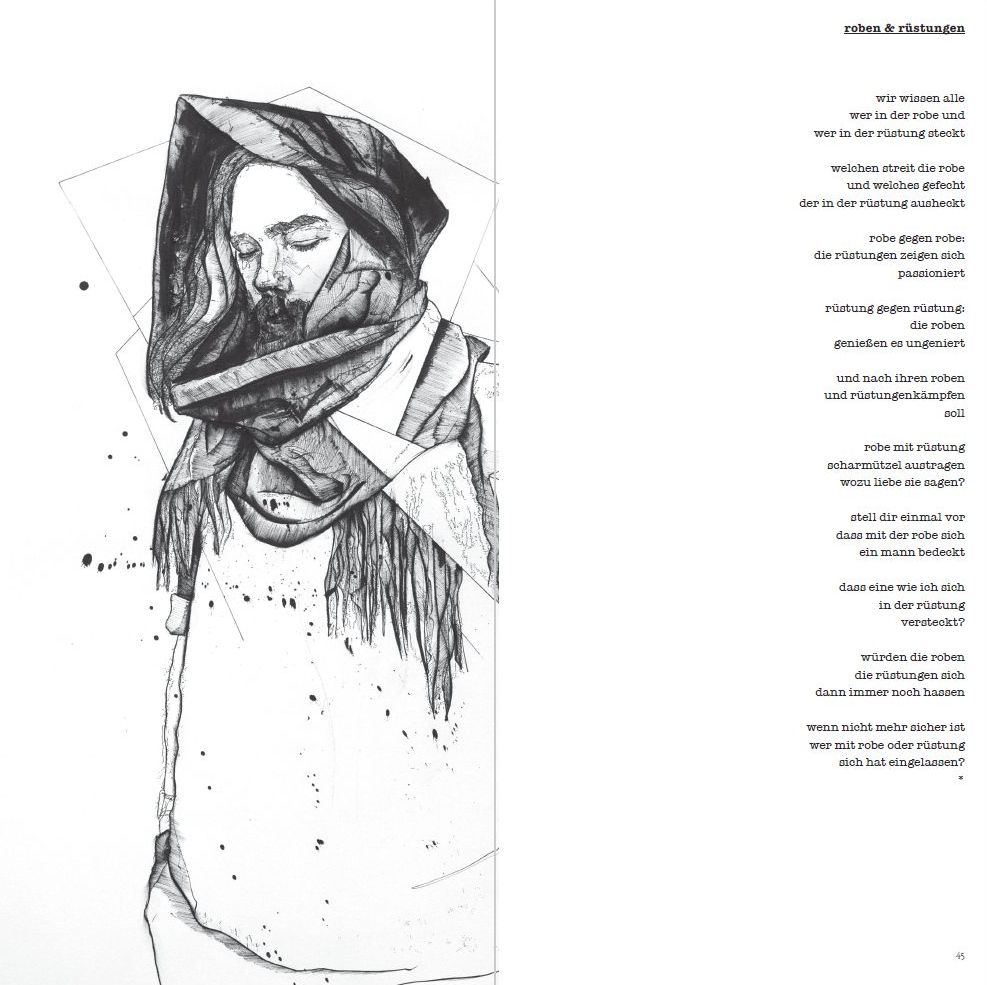

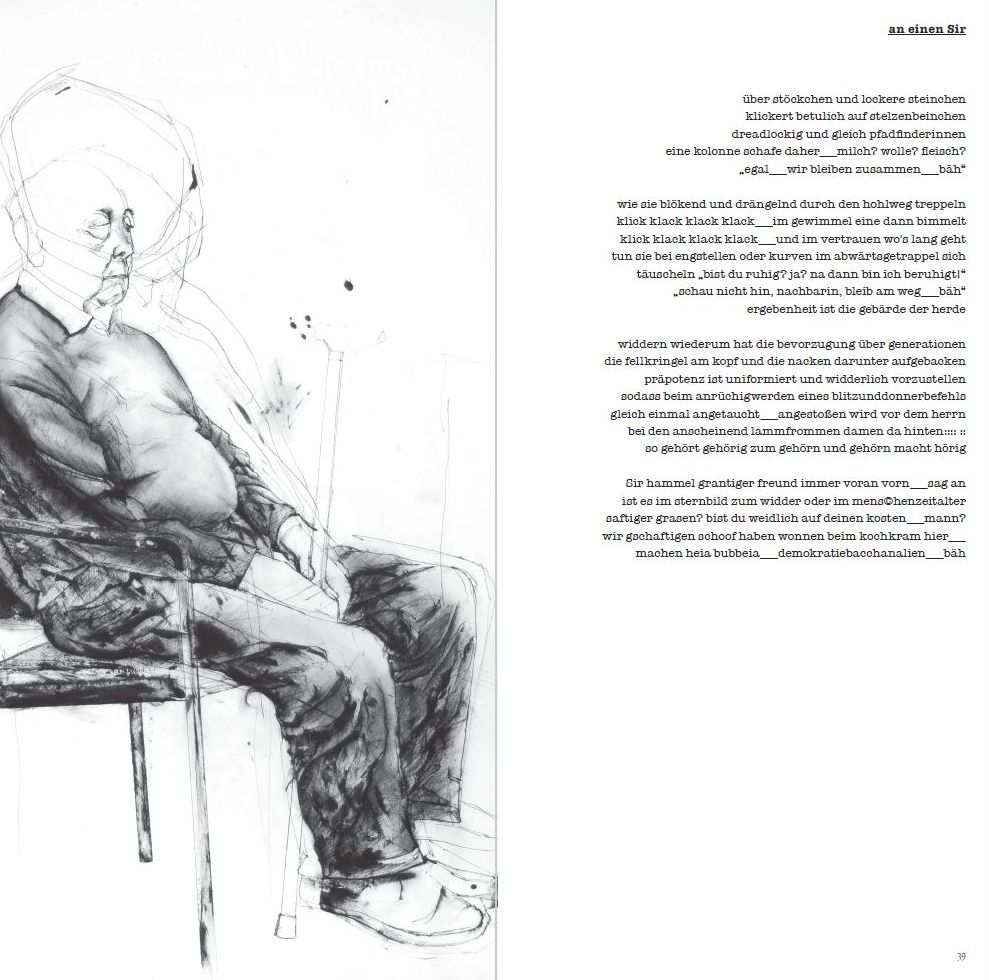

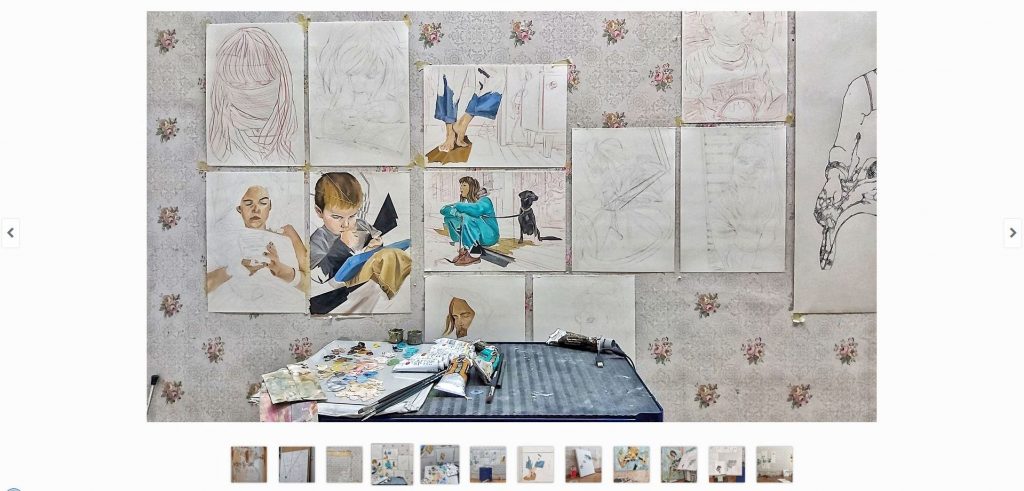

Es sind Themen der Gegenwart, die wir vor uns sehen, persönliche Erfahrungen von Bazant-Hegemark, aber auch gesellschaftspolitische Reflexionen, kleine Skizzen und große Panoramen, unscheinbare Beobachtungen und ausladende Erzählungen. Menschen und ihre Geschichten aus dem unmittelbaren Umfeld des Künstlers tauchen ebenso auf wie in Malerei und Zeichnung transformierte, fragmentierte Medienbilder, etwa der „Black Lives Matter“-Proteste in den USA. Manches können wir leicht erkennen und entschlüsseln, anderes nur vermuten, vieles aber bleibt bewusst im Uneindeutigen und lässt vielfältige Interpretationen zu. Der Künstler kennt und zitiert unaufdringlich aus dem reichen Fundus der Kunstgeschichte, die mit Pathos aufgeladenen Posen und Gesten lassen an die christlich-westliche Bildtradition denken, die geometrisch abstrahierten Körperformen und Gegenstände erinnern an den Kubismus, die sinnlichen Blattornamente, wie sie sich verspielt um Figuren ranken, an den Jugendstil. Auf einem zarten malerischen Hintergrund komponiert Bazant-Hegemark mit klaren Linien und Flächen, mit vegetativen Verzierungen und menschlichen Körpern aufwändige Weltentwürfe und kleinteilige Bildgeschichten, um zugleich diese selbst geschaffenen Ordnungssysteme zu hinterfragen und immer wieder neu aufzubrechen. Menschen und Tiere, Pflanzen und Objekte verlieren ihre in sich geschlossene Entität. Aufgesplittert und verzerrt, in Fragmente zerlegt oder aus ihnen zusammengesetzt, sind sie einem ständigen Transformationsprozess unterworfen und folgen einem vom Künstler definierten Raum- und Zeitgefühl. Ein lustvolles Spiel auch mit der Dialektik von abstrakten, geometrischen Zeichen und weichen figurativen Formen.

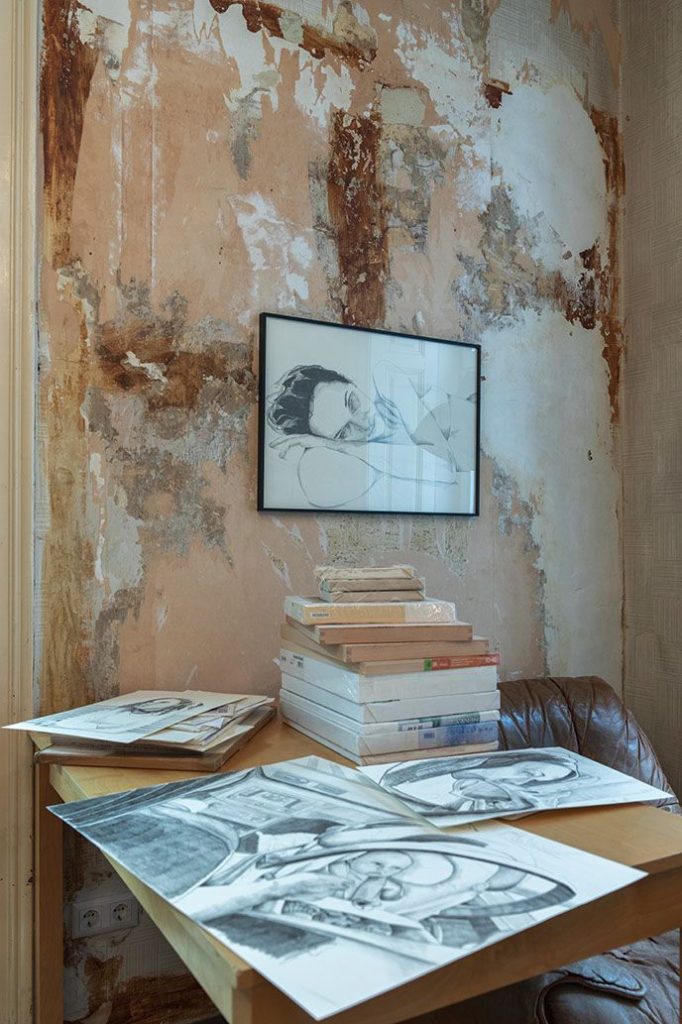

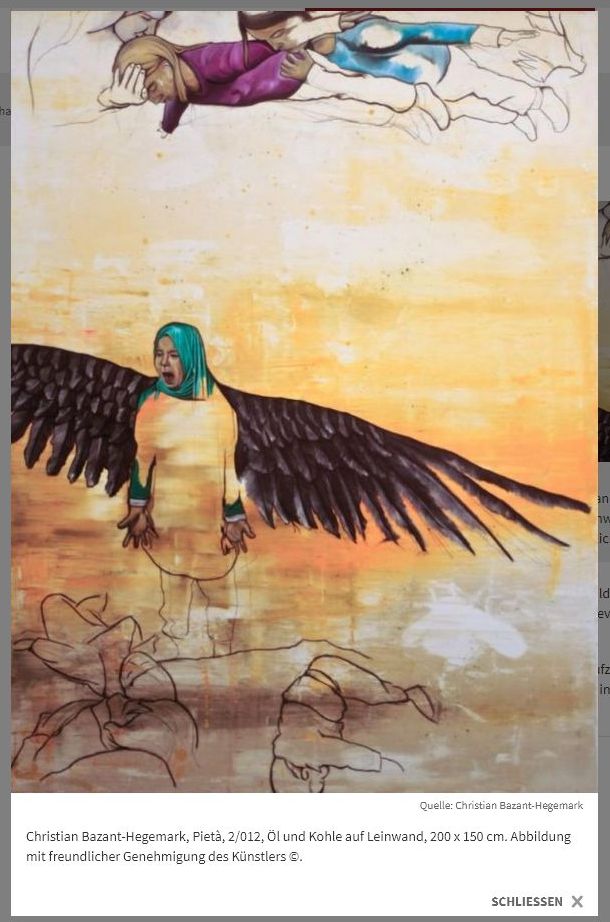

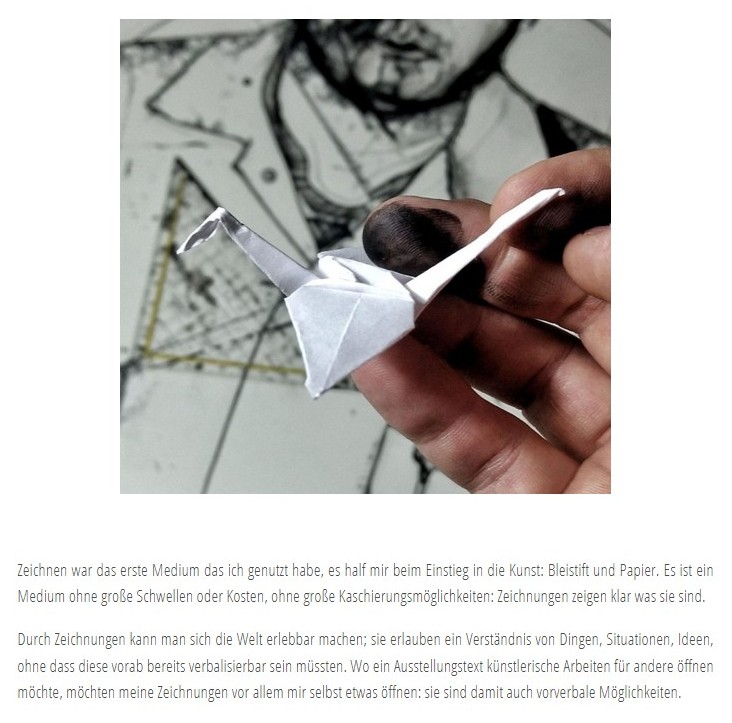

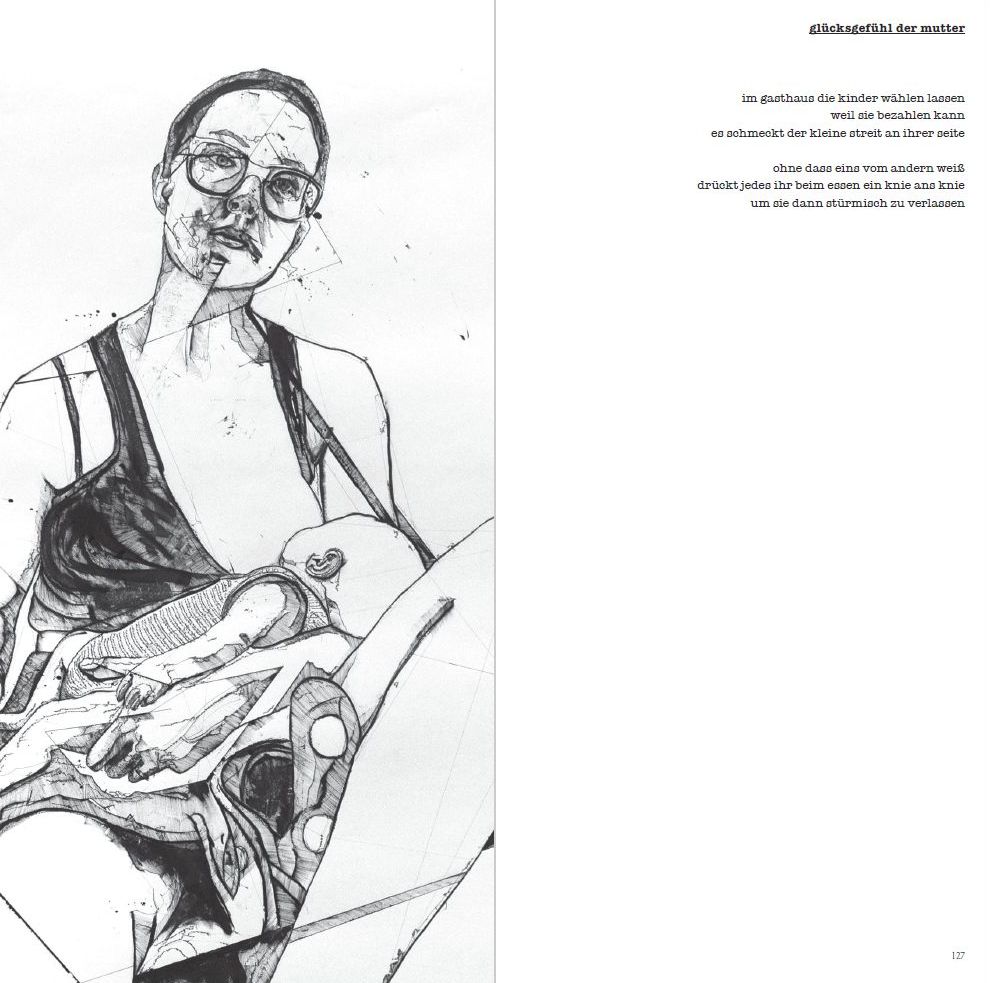

Der Vogel – realistisch wiedergegeben oder auch als Origamifigur – auf der Erde, in der Hand oder in der Luft, die engelsgleichen Flügel als symbolträchtiges Accessoire, die hängenden, schwebenden, fallenden Menschen oder auch in sich gekehrt, ruhend, in Ausstrahlung und Würde gleich Heiligenbildern: Viele Motive erscheinen uns vertraut und fremd zugleich. Bazant-Hegermark lässt sich auch immer wieder von seiner unmittelbaren Umgebung inspirieren und alltägliche Szenen als besonders erscheinen: Ein Mann sitzt in der Küche, eine Frau stillt ihr Kind, eine Hand streicht über ein Klavier. Eindringlich sind auch die kleinen, intimen Studien: ein schnell skizzierter Akt, eine schlafende Frau, ein lesendes Kind. Und doch, auch diese Bilder verströmen eine gewisse irreale Stimmung, die wohl dadurch entsteht, dass uns Betrachter*innen die an sich gewöhnlichen Situationen mit sehr hoher Konzentration und Intensität dargeboten werden.

III.

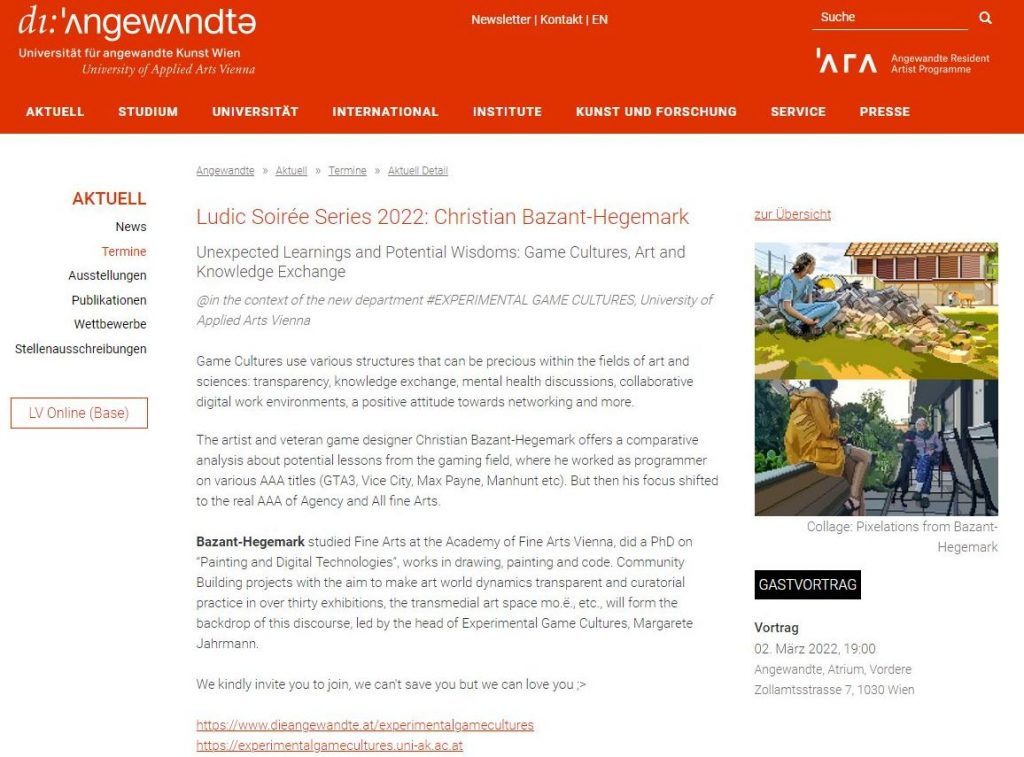

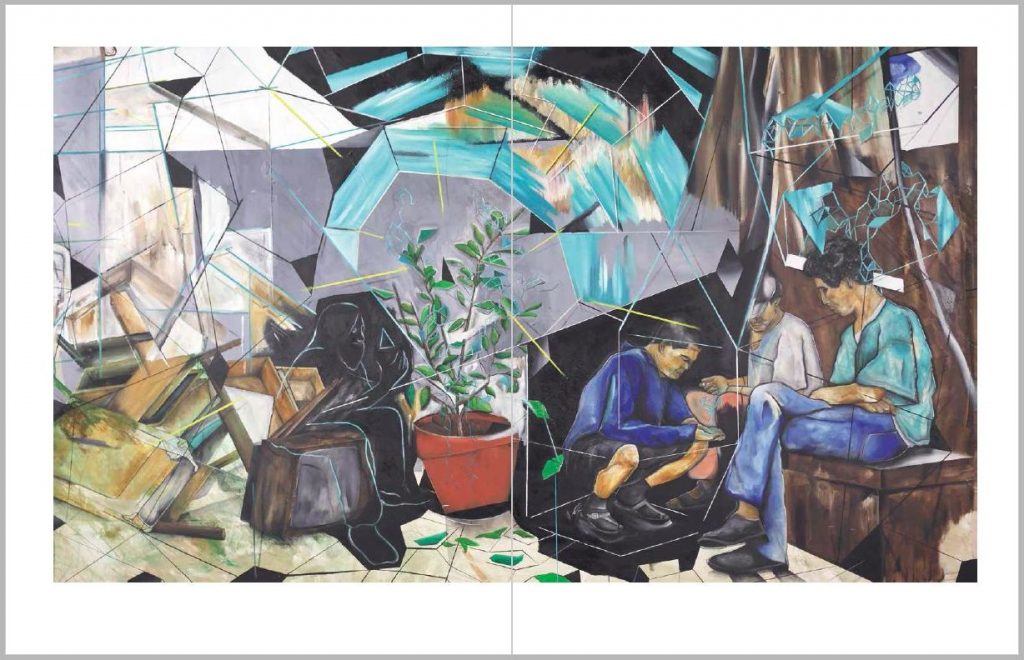

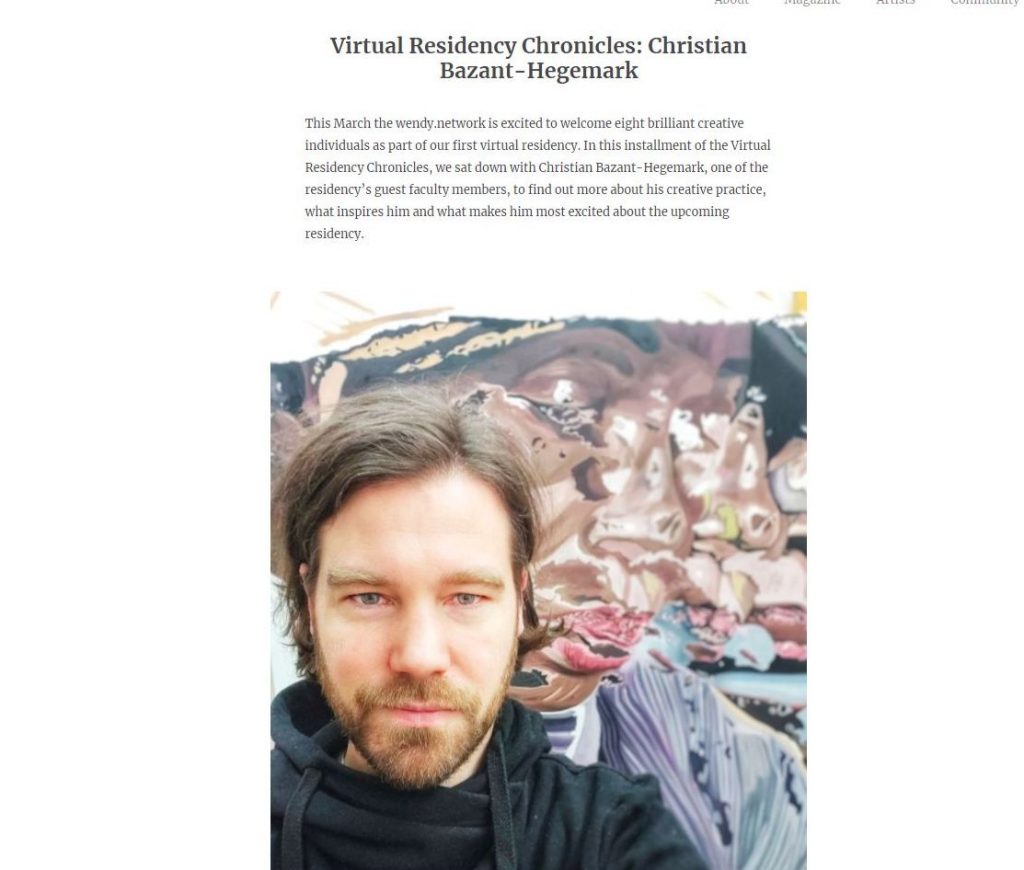

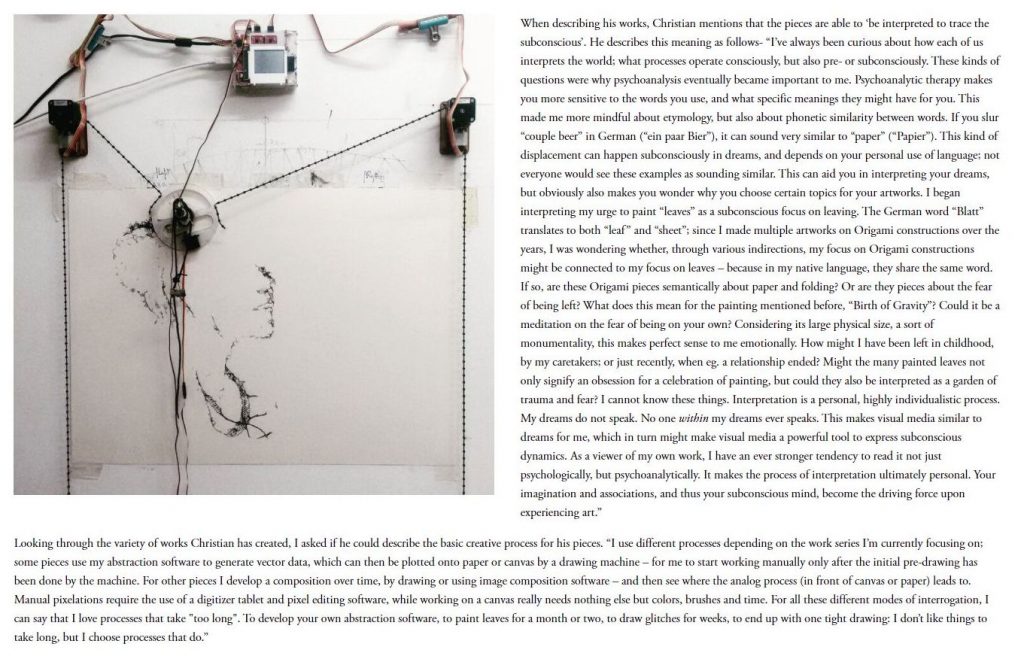

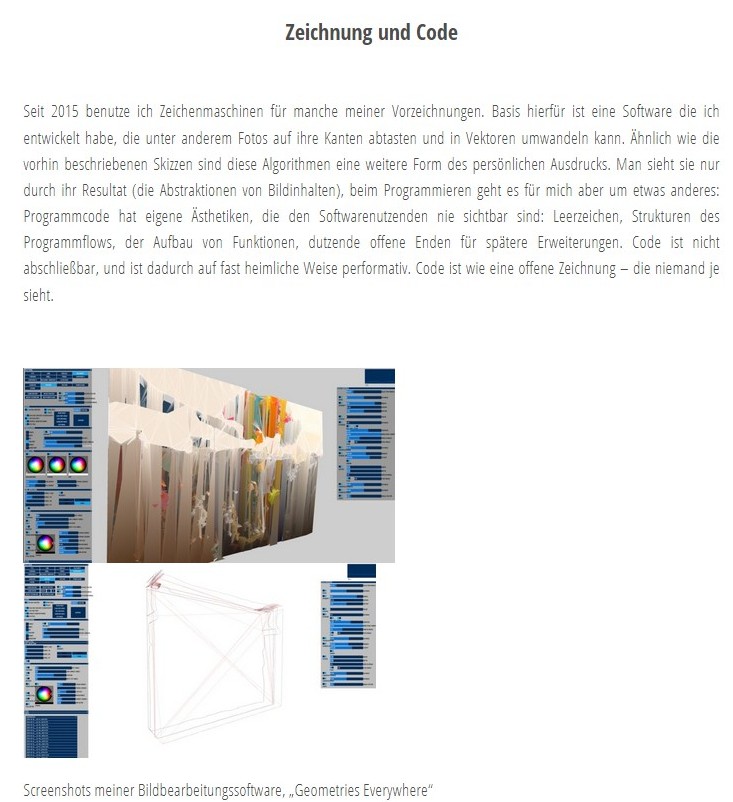

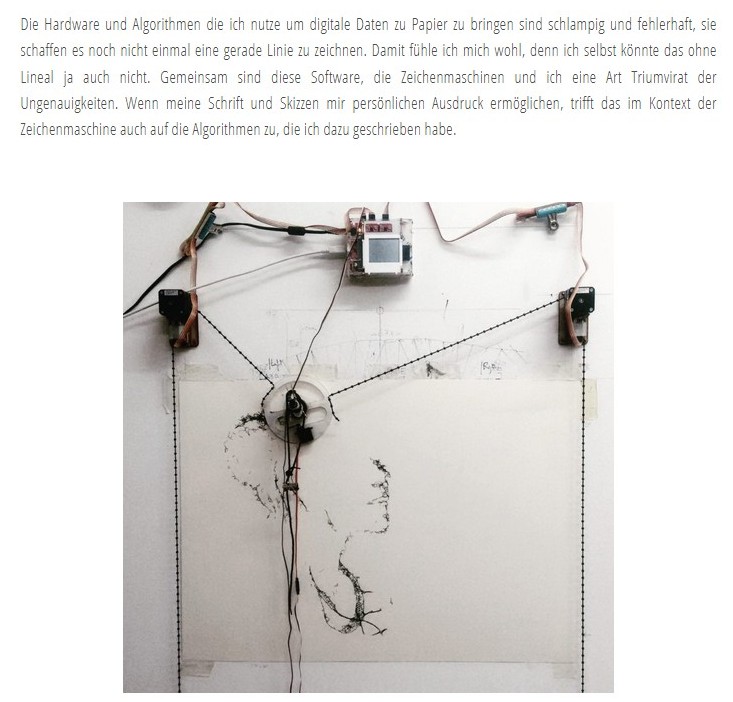

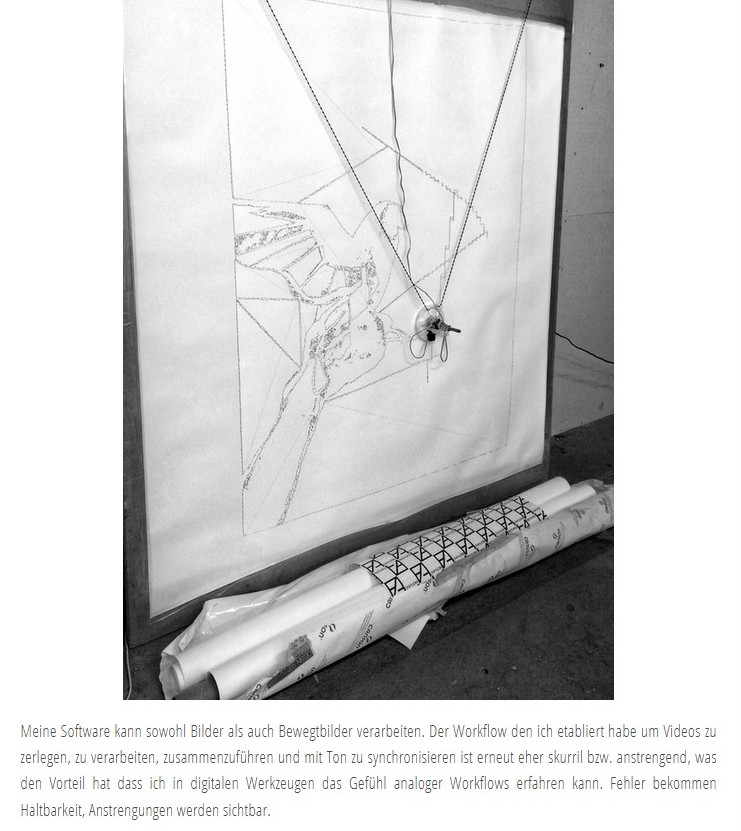

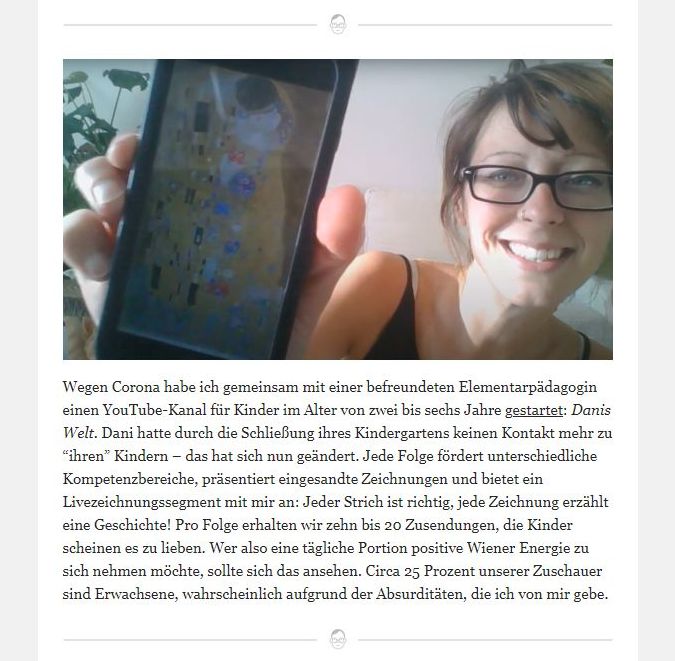

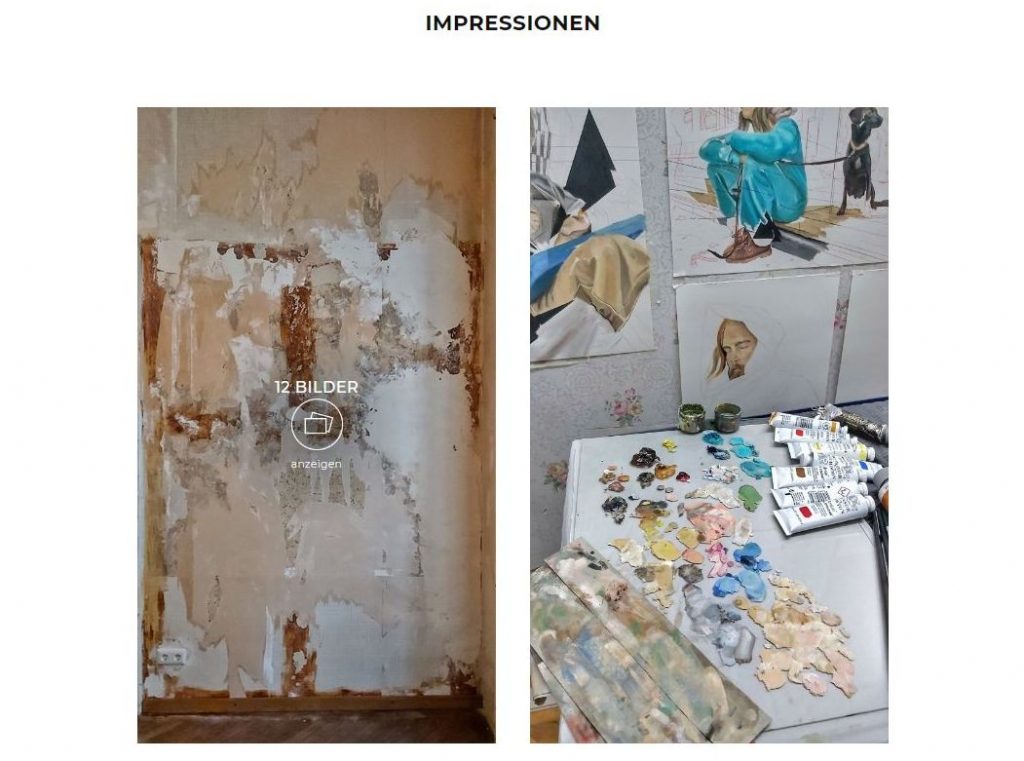

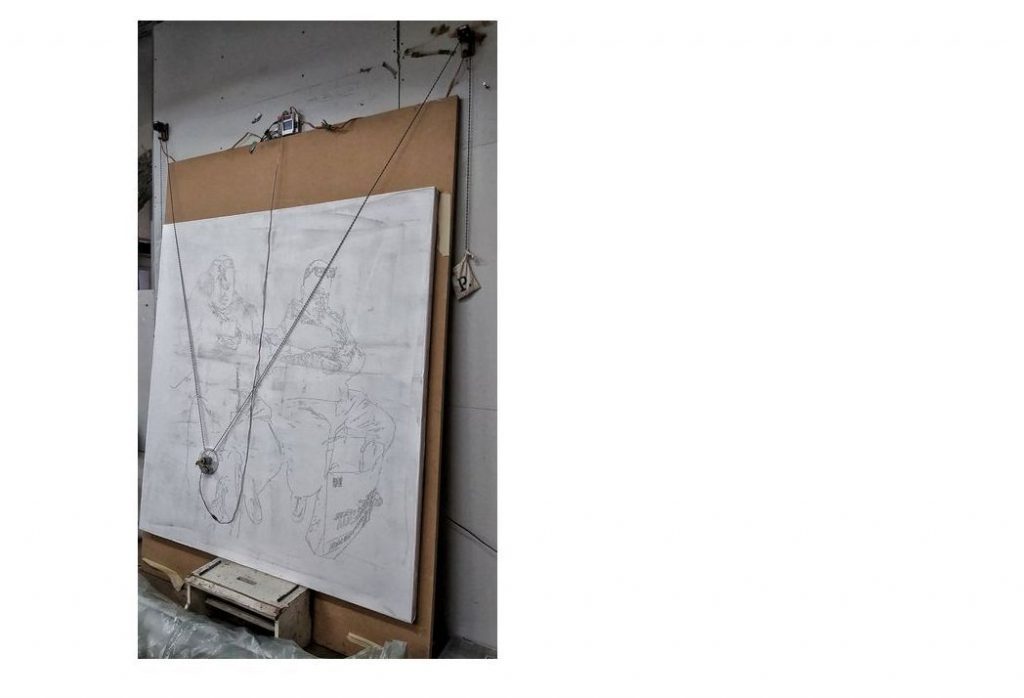

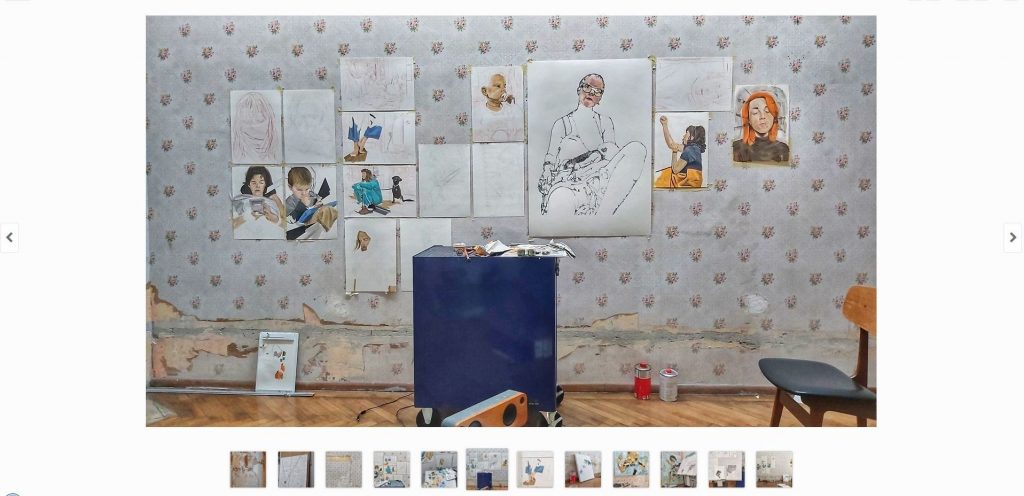

Es sind Techniken der Gegenwart, die mit der Biografie des Künstlers eng verwoben sind. Bazant-Hegemark ist ausgebildeter Informatiker und hat als Videospielprogrammierer gearbeitet, bevor er Kunst studierte. Neben zahlreichen „traditionell“ gemalten Bildern benützt er seit 2015 für einige seiner Werke sogenannte Zeichenmaschinen. Basis hierfür ist „eine Software, die ich entwickelt habe und die unter anderem Fotos auf ihre Kanten abtasten und in Vektoren umwandeln kann“, so der Künstler. Die zur Anwendung kommenden Algorithmen und ihr Resultat, die Abstraktion von Bildinhalten, sind für Bazant-Hegemark eine erweiterte Form des persönlichen Ausdrucks. Dass ein Künstler in seiner kreativen Arbeit auf digitale Unterstützung zurückgreift, ist in unserer multimedialen Gegenwart nicht unbedingt etwas Außergewöhnliches, wohl aber, dass er selbst programmiert und somit die Oberhoheit und den kreativen Einfluss über seine technischen Hilfsmittel behält.

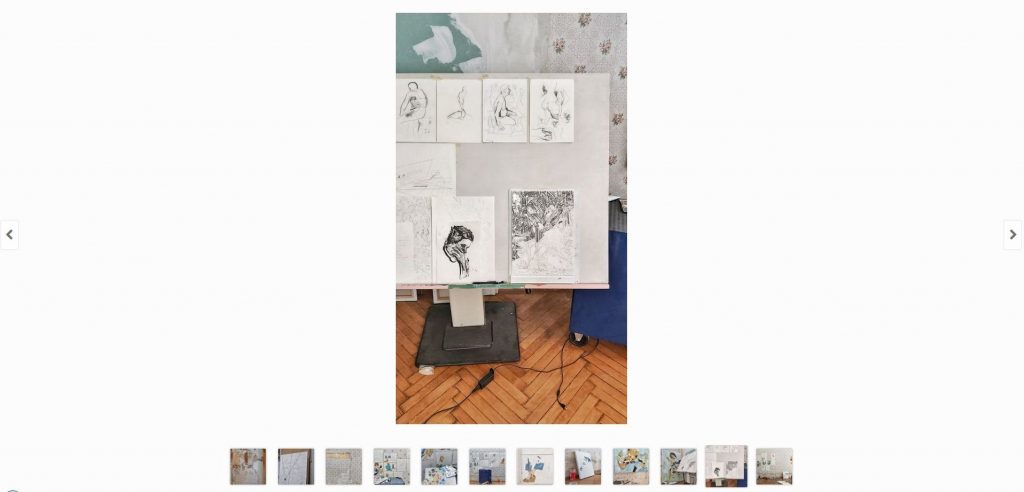

Durch die digitale Manipulation wird das (fotografische) Ausgangsmotiv abstrahiert und in ein neues, artifizielles Bild überführt, bevor es dann, nach dem Übertragungsprozess auf das Papier, vom Künstler mit Tusche weiter bearbeitet wird. Diese mehrstufige Transformation, die dadurch verursachten Verfremdungen und Verzerrungen, aber auch Akzentuierungen und Präzisierungen, relativieren die Bedeutung des konkret Dargestellten, mit dem das Bild bei klarer Erkennbarkeit und eindeutiger Zuordenbarkeit aufgeladen wäre. Auch wenn reale Menschen und Objekte dem Künstler als Vorbild und Inspiration dienen, auch wenn damit verknüpfte reale Geschichten und Begebenheiten am Anfang Pate stehen – in dem vor uns zu sehenden Bild wird, einem Eliminierungsprozess gleich, alles Überflüssige entfernt, bis nichts mehr die Konzentration vom eigentlichen Motiv nimmt, bis keine Details mehr auf spezifische Orte verweisen und sich das Persönliche zur Allgemeingültigkeit öffnet. Der Fokus von Wahrnehmung und Blick wird auf die Essenz der Figur bzw. des Gegenstandes gelegt. Oder mit den Worten von Tim Eitel: „Ich sehe es nicht so, dass ich als Künstler im Alltag banale Dinge auffinde und ihnen dann durch meine Beachtung Bedeutung verleihe […]. Im Grunde ist die Bedeutung schon da: ein besonderer Moment, in dem meine kleine Geste oder ein Gegenstand […] über sich hinausweisen. Und die Schwierigkeit ist, sie später im Atelier mit dem sperrigen Mittel Malerei neu zu rekonsturieren.“[3]

Noch einmal zurück zu den „Zeichenmaschinen“: Im analog zeichnerisch-malerischen Prozess greift Bazant-Hegemark lustvoll in die Komposition ein, er verstärkt oder verunklärt, ergänzt oder übermalt. Es ist ein Arbeiten zwischen aktiv komponieren und auf das Bild reagieren, die Grenzen zwischen analog und digital verschwimmen. „Die Hardware und die Algorithmen, die ich nutze, um digitale Daten zu Papier zu bringen, sind schlampig und fehlerhaft, sie schaffen es noch nicht einmal, eine gerade Linie zu zeichnen“, erzählt der Künstler mit einem Augenzwinkern. „Gemeinsam sind diese Software, die Zeichenmaschinen und ich eine Art Triumvirat der Ungenauigkeiten. Wenn meine Schrift und Skizzen mir persönlichen Ausdruck ermöglichen, trifft das im Kontext der Zeichenmaschine auch auf die Algorithmen zu, die ich dazu geschrieben habe.“ Der Fehler und die Nichtperfektion als Teil des künstlerischen Konzepts – welch ein schöner Gedanke!

IV.

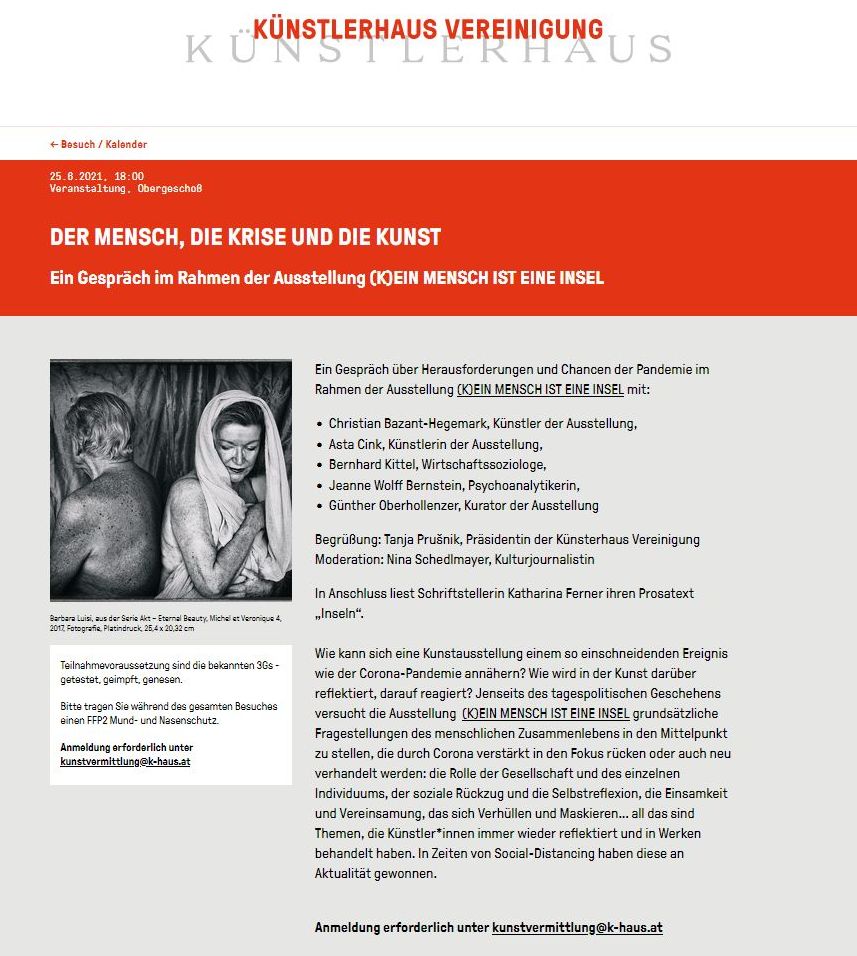

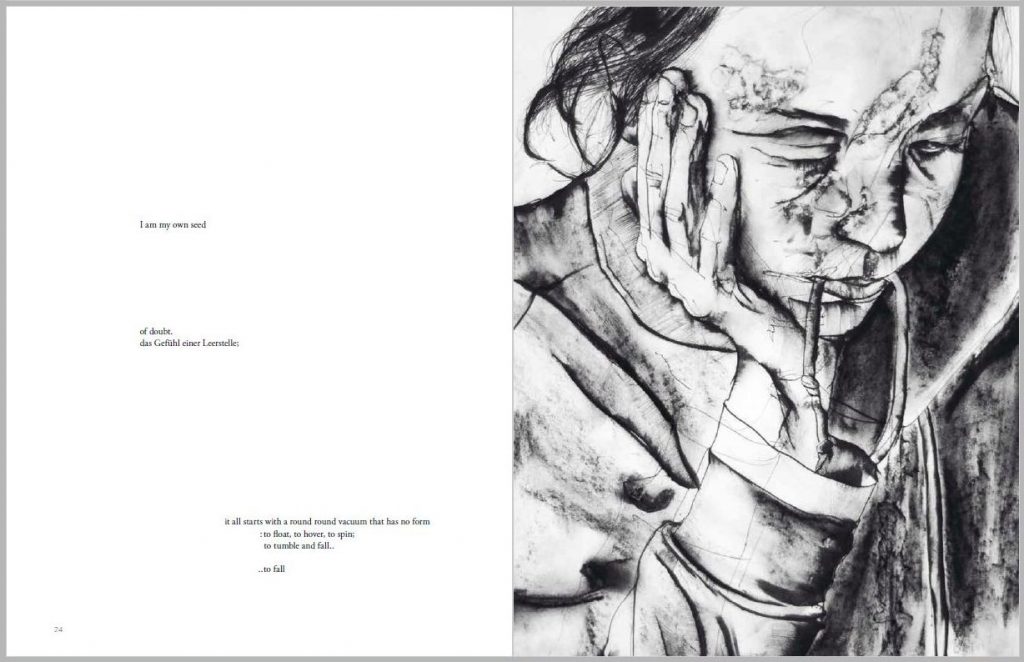

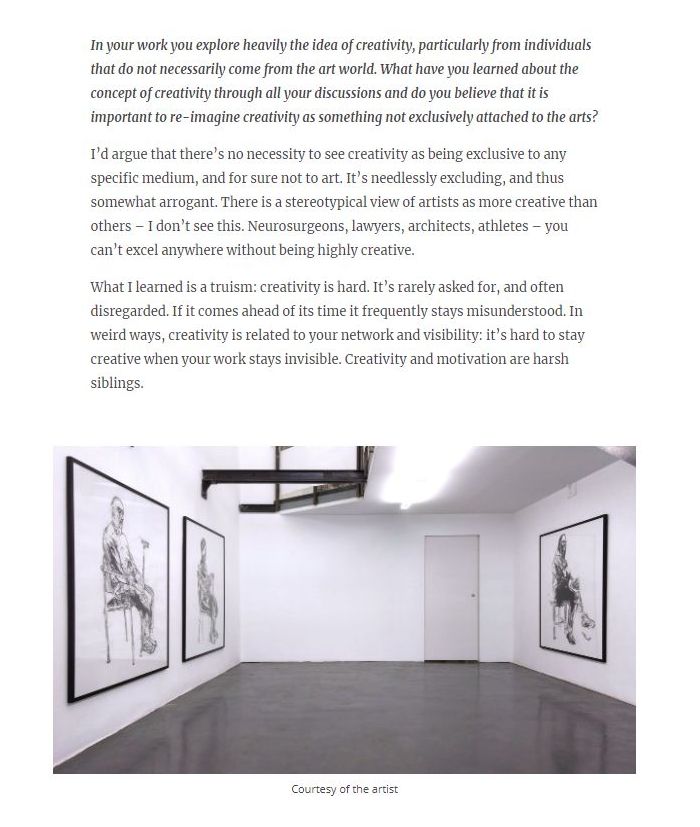

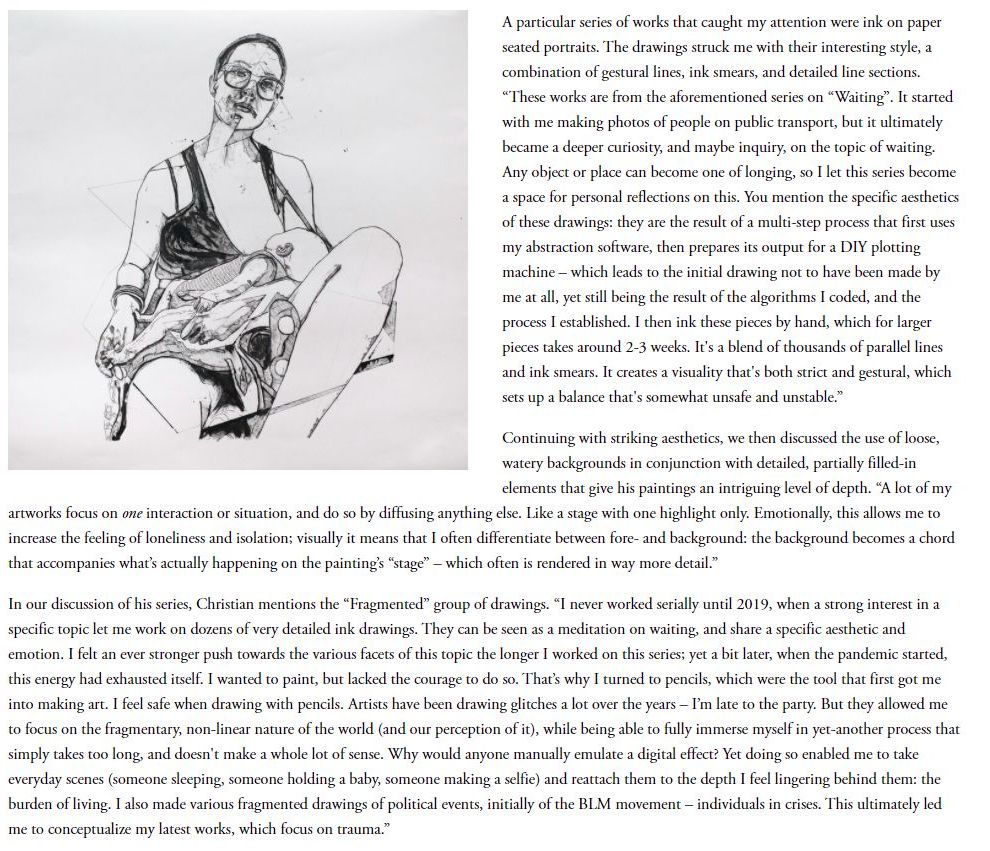

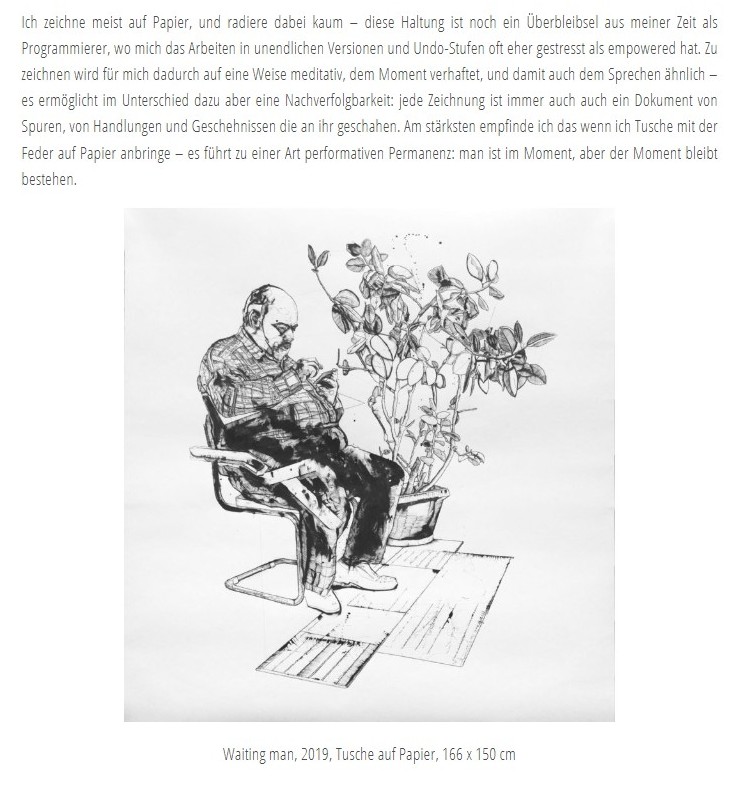

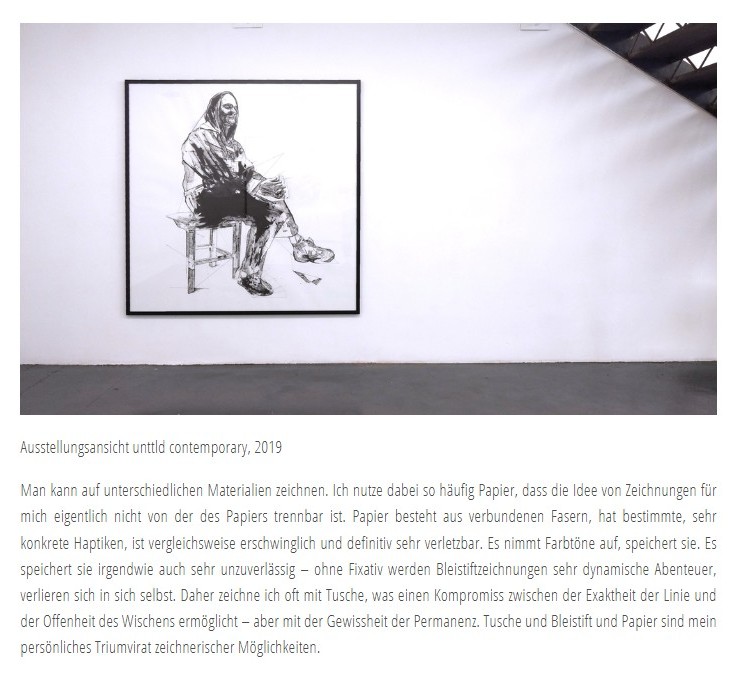

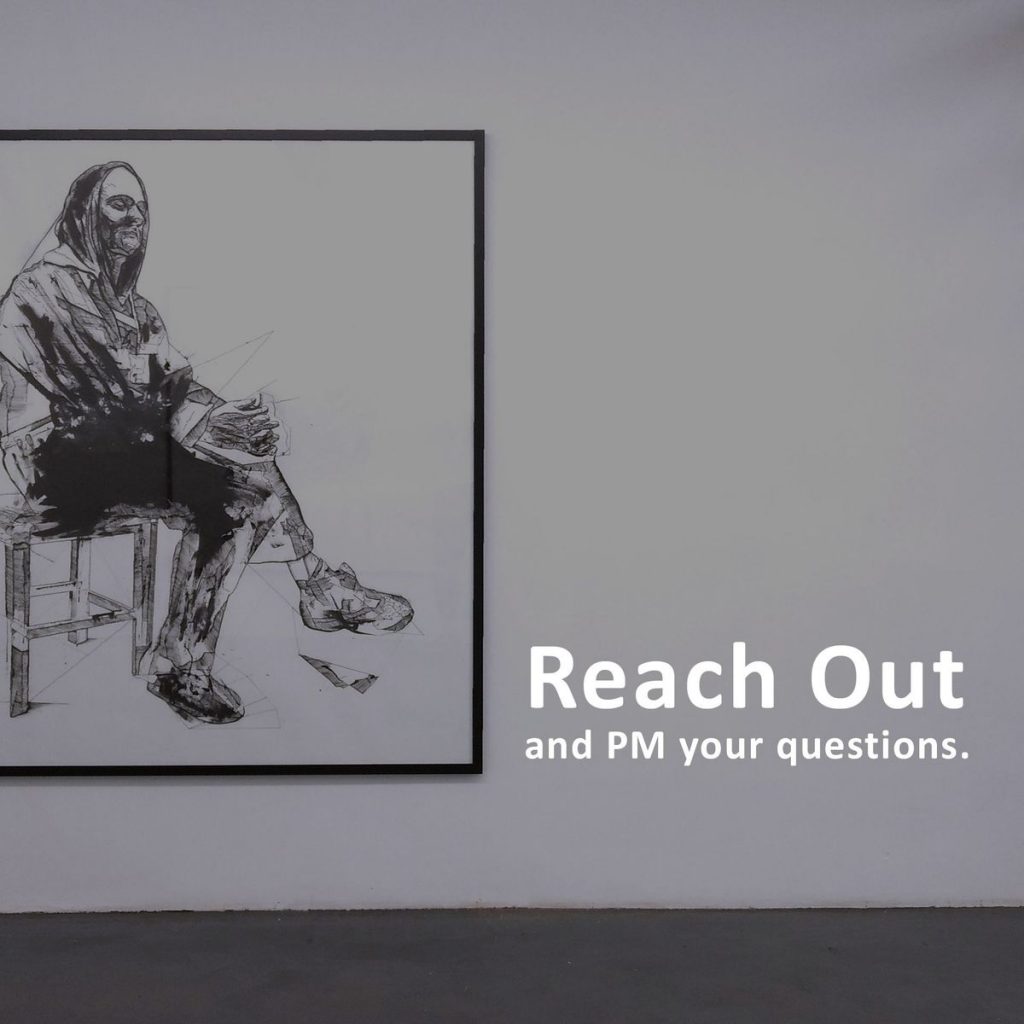

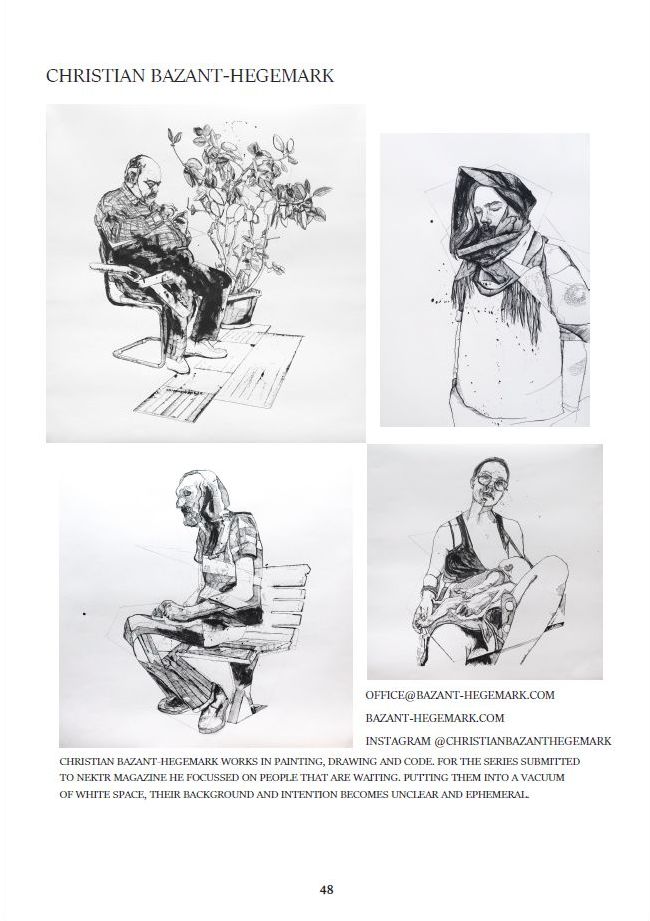

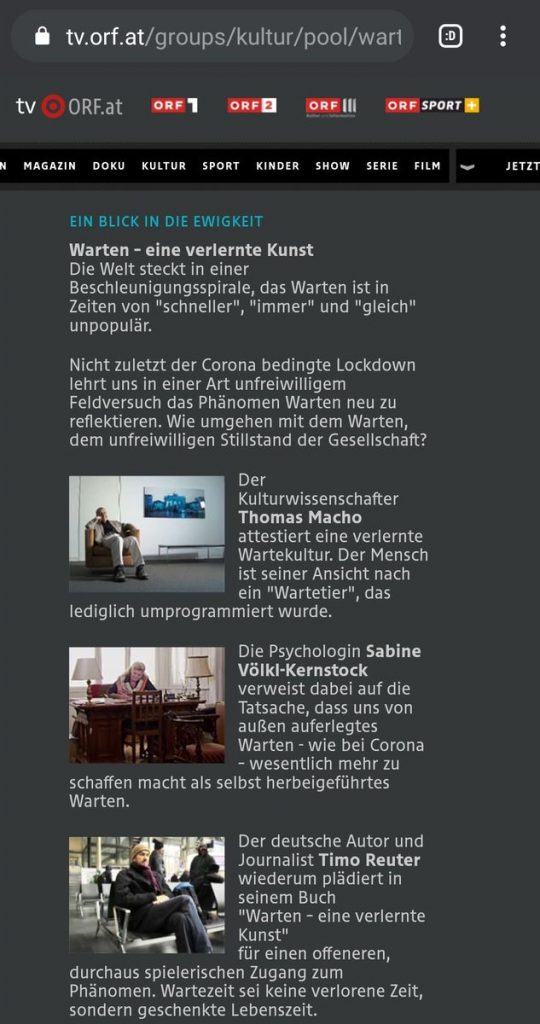

„Das Warten ist ein Zustand ewigen Werdens, man kann nicht wissen, wann es vorbei ist“, sagt Bazant-Hegemark in einem Interview, das im Rahmen eines Fernsehbeitrags über Kunst in Zeiten des Stillstands entstanden ist.[4] Der Künstler hat kurz vor dem ersten Corona-Lockdown eine Serie an großformatigen Zeichnungen mit dem Titel „Waiting“ (2019) geschaffen. Intim und theatralisch zugleich zeigt er Menschen, die, auf sich selbst zurückgeworfen, in einem unbestimmten Wartezustand verharren. Ein in sich gekehrtes Innehalten und Verharren im Selbst, schön und schmerzlich zugleich. Und beinahe visionär.

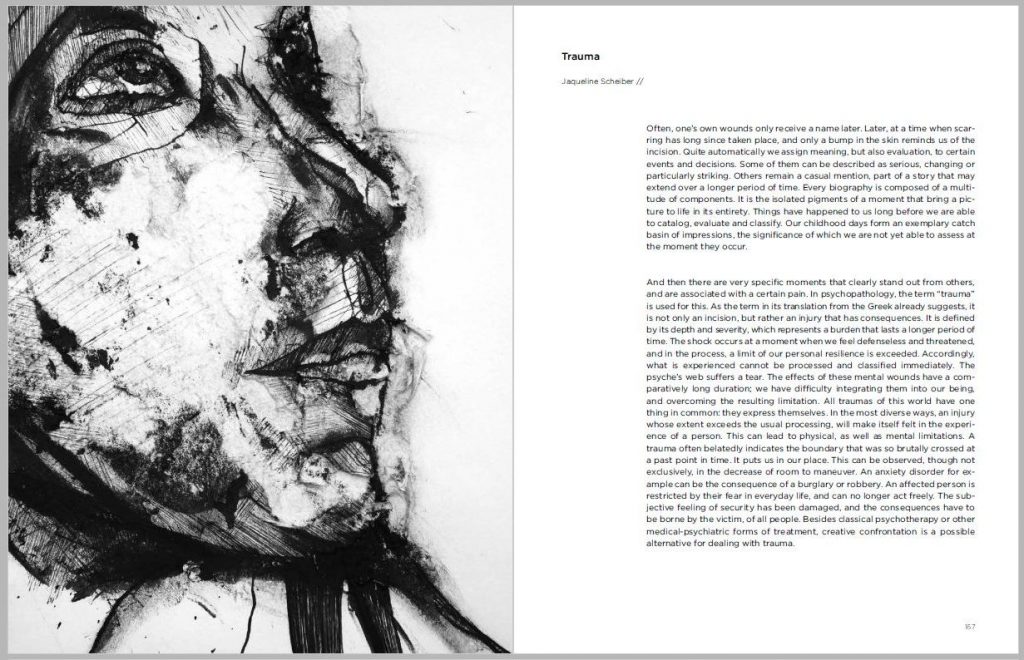

Viele Werke verhandeln die in die Welt geworfene Existenz, die Einsamkeit und Kommunikationslosigkeit, den in sich gekehrten, versunkenen Menschen. Ist in ihnen das titelgebende „Trauma“ zu finden? Sehen wir vor uns die Kunst eines leidenden, traumatisierten Künstlers, der sich über seine Werke im Sinne einer Selbsttherapie auszudrücken versteht? Ein Künstler, der uns an seiner gequälten Seele teilhaben lässt, sodass er – wie vielleicht auch wir – daran genesen mögen? Dieses gern strapazierte Klischee möchte Bazant-Hegemark nicht bedienen. Für seine künstlerische Arbeit wäre es einengend und für die so entstehenden Werke abträglich, unmittelbar eigene Schrecknisse zu bebildern. Und doch kann und darf Kunst auch aus dem Trauma heraus entstehen. Ein Widerspruch? Nicht unbedingt. „Es sind keine Abbildungen meiner Traumata“, betont der Künstler, „aber es geht fast immer um sie. Sie sind das Substrat“. Die Werke können nicht losgelöst vom Menschen Bazant-Hegemark gesehen werden, sind sie doch „die Konsequenz einer Lebenshaltung, die sich auch stark durch solche Schrecken gefestigt hat“. Der Künstler spricht treffend von seinen Bildern als „Zeugen“, die Traumatisches nicht direkt abbilden, aber indirekt auf Aspekte des Unterbewusstseins verweisen. Diese bleiben stets unklar oder „schummrig“ und lassen vielfältige Interpretationen zu, sodass wir Betrachtenden uns nie sicher sein können, wie die Dinge wirklich sind.

Die Ausstellung bedient auch nicht erwartbare künstlerische Entsprechungen von Traumata: Wir sehen keine Malereien in düster grauem Farbenklang, keine zusammengekauerten, im Dunkel hockenden Menschen, keine gequälten, schmerzverzerrten Gesichter. Derart plakative Stilmittel entsprechen kaum dem im Unbewussten angesiedelten Leiden oder konterkarieren dieses sogar. Wenn Bazant-Hegemark in seinen Werken psychologische Zustände behandelt, dann passiert das nicht vordergründig und stets mit dem Wissen, dass diese nur schwer beschreibbar, durch Zeichnung oder Malerei nur bedingt darstellbar sind.[5] „Die Wahrheit einer Person bildet sich nicht nur in ihrer Oberfläche ab“, so der Künstler. „Der introspektive Blick der Dargestellten verweist auf eine innere Kommunikation, der wir Betrachtenden nicht zuhören können.“ Seine Bilder gehen über die sichtbare Oberfläche hinaus, mit Feingefühl und subtiler Komposition gelingt es ihm, Werke zu erschaffen, die die seelische Erschütterung seiner Protagonist*innen spürbar macht – ohne sie zu verraten oder bloßzustellen.

„Der Grundcharakter des Malens, dem ich mich verschrieben habe, besteht darin, dass man über eine bestimmte Situation einen Bann ausspricht oder verhängt“, betont der deutsche Maler Neo Rauch. „Das heißt, ich bringe eine Situation zur Ruhe, die unter Umständen von ihrer Charakteristik her unangenehm oder bedrohlich sein kann. […] Das ist das enorme Potenzial der Malerei, dass ich etwas Böses oder etwas Krankes malen kann, indem ich ein hochvitales Stück Malerei produziere. Die Malerei triumphiert über das, dem sie sich zuwendet.“[6] Bazant-Hegemark vereint Werke unter dem Titel „Trauma“, ohne dieses offen zu zeigen. Gelungene Kunst ist nie reine Illustration. Sie ist weit mehr als das.

So nehmen wir Betrachter*innen teil an filigranen, oft sonderlichen, aber niemals beliebigen oder langweiligen Weltenwürfen, die ob des technischen Könnens beeindrucken und des inhaltlichen Ideenreichtums faszinieren – ein bildnerischer Kosmos, in dem Menschen durch geometrische Linien und ornamentale Muster miteinander verbunden sind und doch für sich alleine bleiben, in dem die Protagonist*innen selten etwas tun und in einem Zustand des Verharrens nicht vordergründig mit uns interagieren und dennoch (oder gerade deshalb) durch Uneindeutigkeit und Rätselhaftigkeit fesseln, in dem durch die Stilllegung eines Moments, einer Geschichte oder Begebenheit eine fühlbare Entschleunigung eintritt, die im besten Fall auch auf uns Betrachtende überspringt. Seine Werke seien „emotionale Möglichkeitsräume“, so Bazant-Hegemark, die darauf abzielen, „individuell zu berühren“. Schön gesagt, denn gerade im Zeitalter des Überflusses digitaler Bildreproduktion bietet die Malerei alternative Möglichkeitsräume an, um sich der Komplexität unserer Welt anzunähern. Der Maler zeigt uns seinen autonomen, reflexiven Standpunkt inmitten der oft anonymen Beliebigkeit und Austauschbarkeit medialer Bilder, von dem aus sich dieser als Subjekt wahrnimmt und verortet. Lassen wir uns auf seine Welt ein, werden wir reich belohnt.

_____

Falls nicht anders angegeben, stammen die Zitate von Christian Bazant-Hegemark aus Gesprächen mit dem Autor und persönlichen Texten des Künstlers.

[1] So charakterisiert Tim Eitel seine Malerei. Mir scheint dieses Zitat aber auch passend zu sein, um die Kunst von Christian Bazant-Hegemark zu beschreiben. Tim Eitel im Gespräch mit Günther Oberhollenzer, in: „Tim Eitel: Besucher“, Katalog zur gleichnamigen Ausstellung im Essl Museum, Klosterneuburg / Wien 2013, Seite 10

[2] Robert Fleck, „Die Ablösung vom 20. Jahrhundert. Malerei der Gegenwart“, Passagen Verlag, Wien 2013, Seiten18f., 23–27. Fleck nennt als Beispiele für das „Floaten“ des Bildraums u.a. Georg Baselitz und Peter Doig.

[3] Ebenda, Seite 10

[4] Christian Bazant-Hegemark, zit. nach einem Bericht von Markus Greussing, „Warten – eine verlernte Kunst“, Reportage für den „Kulturmontag“ im ORF2, Erstausstrahlung am 25.05.2020

[5] Die Arbeiten unter dem Titel „Trauma“ zu subsumieren stand auch nicht am Anfang des künstlerischen Prozesses, sondern an dessen Ende, als es darum ging, für die getroffene Werkauswahl einen Ausstellungstitel zu finden.

[6] Neo Rauch, zit. nach: Rosa Loy und Neo Rauch im Gespräch mit Günther Oberhollenzer, in: „Rosa Loy & Neo Rauch: Hinter den Gärten“, Katalog zur gleichnamigen Ausstellung im Essl Museum Klosterneuburg / Wien, Prestel Verlag, München 2011, Seite 190